miss augusta spottiswoode

Subject Name: Miss Augusta Spottiswoode (b 1823 – d 1912)

Researcher: Diann Arnfield

MEMBER OF THE GUILDFORD UNION BOARD OF GUARDIANS FOR SHERE

April 1881 – April 1898

Augusta Spottiswoode – the “Children’s Friend”

‘The children’s friend’ was the name given to Augusta Spottiswoode following a lifetime of help and care for children, most especially during her time as the first elected woman officer of the Guildford Board of Guardians.

Following a privileged upbringing which saw her presented to the young Queen Victoria, Augusta became aware of the hardships of life faced by many people through an innovative scheme run by her father at his printing works. She was an early supporter of women being given the right to vote, and after moving permanently with her sister Rosa to their late parents’ home in Shere, they did all they could to help the underprivileged in their district.

During Augusta’s close to 17 years with the Guildford Board of Guardians, she backed the somewhat controversial scheme for the emigration of pauper children to Canada but also helped others in the West Surrey area, regularly employing inmate boys and girls in her own home at the start of their working lives.

Augusta’s other achievements included hosting charitable events, providing financial backing for education and church developments as well as entertaining Guildford Union inmates annually at her home. Even the improvement of Shere’s water supply came about through her efforts.

Early years

Augusta Spottiswoode was born on 15th August 1823, in Hampstead, London, the youngest daughter of Andrew and Mary Spottiswoode née Longman. She was baptised on 17th October 1823 at Hampstead’s St John’s Church. Augusta had two older sisters, Elizabeth and Rosa, and two younger brothers William and George 1-8.

Augusta Spottiswoode was born on 15th August 1823, in Hampstead, London, the youngest daughter of Andrew and Mary Spottiswoode née Longman. She was baptised on 17th October 1823 at Hampstead’s St John’s Church. Augusta had two older sisters, Elizabeth and Rosa, and two younger brothers William and George 1-8.

Augusta was undoubtedly from a very privileged and well-off family. Her father Andrew and his  brother Robert had overseen the printing firm Eyre & Spottiswoode since 1819, with the company having been the King’s Printer since 1767. Andrew was also involved in politics as he was elected MP for Saltash in 1826 and then Colchester in 1830 but following complaints regarding conflict of interest with his work as the King’s Printer, he was forced to stand down 9.

brother Robert had overseen the printing firm Eyre & Spottiswoode since 1819, with the company having been the King’s Printer since 1767. Andrew was also involved in politics as he was elected MP for Saltash in 1826 and then Colchester in 1830 but following complaints regarding conflict of interest with his work as the King’s Printer, he was forced to stand down 9.

After his brother Robert died in 1832, Andrew continued to run the business, becoming the Queen’s Printer in 1837 on the accession of Queen Victoria. When Andrew retired in 1855, Augusta’s brothers William and George took over, with the family remaining in control of Eyre & Spottiswoode until well into the 20th century 10.

Spottiswoode Homes

Augusta and her four siblings had all been born in London, but around 1830, their father Andrew had a new home, Broome Hall, built near Dorking, Surrey. The family would have divided their time between here and properties in London – the 1841 Census showed them living at 17 Carlton House Terrace, overlooking St James’ Park, London. This had been the home of  Lord Cardigan, who in 1854 would lead the fateful Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War 11, 12.

Lord Cardigan, who in 1854 would lead the fateful Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War 11, 12.

Broome Hall is now a Grade II listed building with more recent owners including actor Oliver Reed in the 1970s.

Presentation at Court

Wherever Augusta was living at the time, her education would almost certainly have been provided by a governess. Apart from the three basics of reading, writing and arithmetic, Augusta and sisters Elizabeth and Rosa would have been taught skills such as sewing, drawing, dancing, French conversation, how to play the piano and ‘etiquette proper to young ladies’ 14.

The next stage in their development was ‘coming out’ into Society at the age of 18, which, no doubt through their father’s royal connection as the Queen’s Printer, meant that the three Spottiswoode young women were all ‘Presented at Court’ to Queen Victoria. For Augusta, accompanied by her mother, this took place six weeks before her 20th birthday on 29th June 1843 in the Drawing Room of St James’ Palace 15.

‘Presented at Court’ to Queen Victoria. For Augusta, accompanied by her mother, this took place six weeks before her 20th birthday on 29th June 1843 in the Drawing Room of St James’ Palace 15.

Augusta and her sister Rosa met Queen Victoria again when they were invited to celebrate the Queen’s 26th birthday on 24th May 1845 at St James’ Palace. This event attracted much attention from the newspapers, devoting columns of print about who was there and what they were wearing. Augusta and Rosa were dressed similarly which was described in lavish detail: ‘Costume de cour, composed of a train of rich blue glacé silk, trimmed with tulle, crepe lisse, and ribbon: body and sleeves a la Sevigne: double skirt of white tarletan, with agraffes of flowers over glacé silk. Coiffure of ostrich feathers and pearls: lappets of rich lace’ 16.

Despite the Spottiswoode family moving in such high circles, they were not immune to the effects of daily life. One of the string of Asiatic Cholera epidemics which struck London and many other parts of the country in the mid-19th Century claimed the life of Augusta’s eldest sister Elizabeth in 1849, aged just 29 17.

Spottiswoode family’s innovative project

Augusta and Rosa remained with their family, living at the time of the 1851 Census at 12 James Street, Westminster. Their father Andrew was still running the printing business close by at New Street Square, with their brothers William and George both employed by him 18. Neither 27-year-old Augusta nor Rosa were noted with any occupation, but they became involved in a remarkable forward-thinking project run by the family at the printing works.

Around 100 boys were employed in the machine and warehousing department, so the Spottiswoodes decided to set up a school within the works to improve the education of those boys. Hours were set aside during which the boys were taught basic subjects such as geography, history and mathematics – Augusta’s brother William was one of the country’s leading mathematicians at this time 19, 20. The boys were also set examinations, which in 1854 were conducted in the Eyre & Spottiswoode lecture room in front of an audience including the Bishop of London. At the end of the examination, prizes were handed out by the Bishop, followed by co-publisher George Eyre saying that the boys were to be congratulated for ‘having so kind and considerate a friend in Miss Augusta Spottiswoode, no inconsiderable portion of whose time was devoted to their comfort and well-being’ 21.

The Spottiswoodes were also intent in looking after their other employees. In 1853, George decided that the office should close on Saturday afternoons so that the staff could enjoy some leisure time. He set up a company cricket team in which he also played, followed later by football and rowing clubs 22.

Another venture was the Spottiswoode Choral Society of which Augusta, Rosa and their mother were members. At a charity concert given by the Society in 1861, it was reported that ‘Mrs Andrew Spottiswoode presided at the pianoforte, and the Misses Spottiswoode … performed their respective parts efficiently in the chorus’ which was followed by ‘introduction of a part song, composed for the occasion, by Miss Augusta Spottiswoode’ 23.

A move to Drydown House, Shere

The 1861 Census showed Augusta was a visitor to her maternal aunt Frances and husband Reginald Bray at Fir Hill House, Shere 24. She was not shown to be in employment and was  almost certainly still living with her parents and siblings in Westminster at 12 James Street 25. Her father Andrew had now retired from the printing business with his son William now in charge. Around this time, Andrew acquired Drydown House in Shere as the family’s country residence, where Augusta and her family lived from 1862 26, 88.

almost certainly still living with her parents and siblings in Westminster at 12 James Street 25. Her father Andrew had now retired from the printing business with his son William now in charge. Around this time, Andrew acquired Drydown House in Shere as the family’s country residence, where Augusta and her family lived from 1862 26, 88.

Andrew died in London in February 1866 aged 79 27. While Augusta and Rosa’s brother George inherited the family properties including Drydown House, the sisters received equal shares in their father’s four Life Assurance Policies and in the London Gas Light Company, the sum of which would have ensured they would both have been financially secure for life.

Augusta and Women’s Suffrage

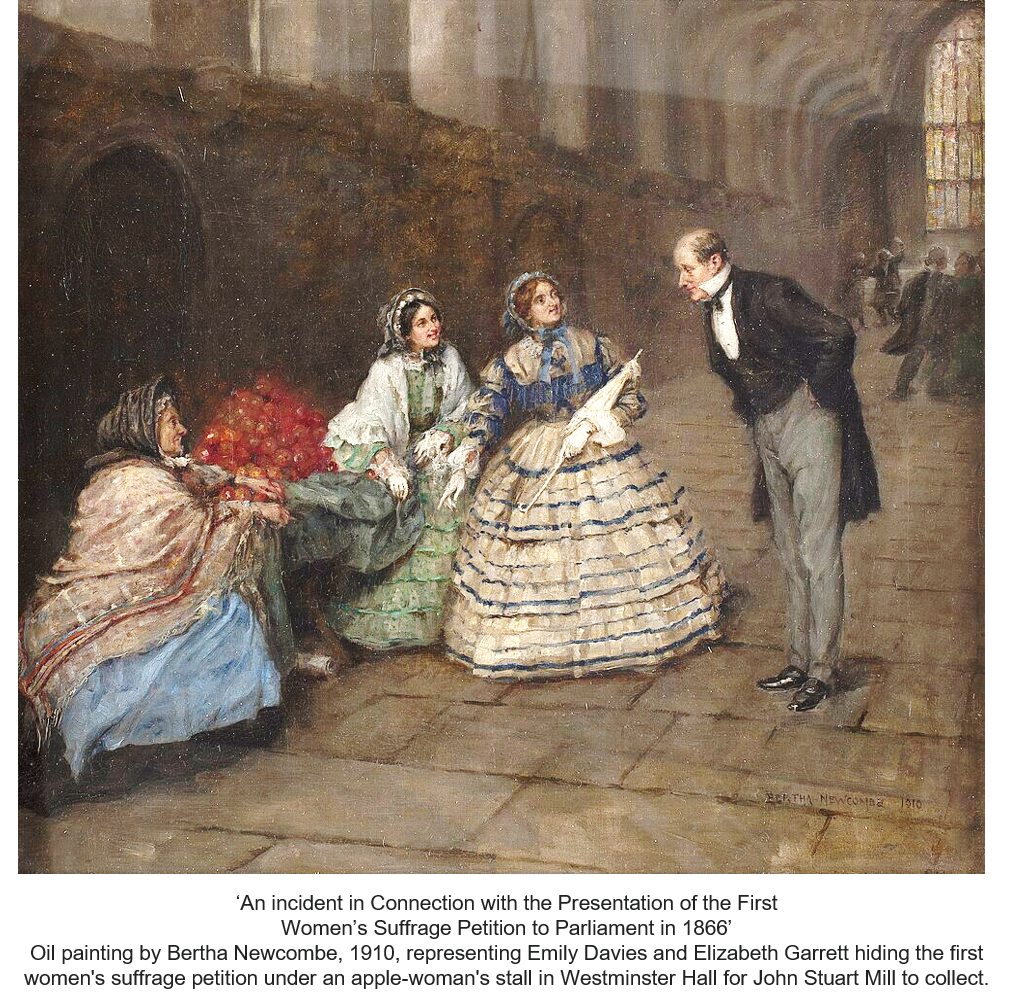

During the second half of the 19th century, women across the country became engaged in a determined effort for their right to vote. The London National Society for Women’s Suffrage (LNSWS) initiated one of the early campaigns. Augusta was one of the 1,521 signatures on the first petition for women’s suffrage which was presented to Parliament by Augusta’s City of Westminster MP John Stuart Mill on 7th June 1866 28. Because it was so controversial, the petition was said to have been hidden under the stall of an apple seller for Mr Mill to collect.

During the second half of the 19th century, women across the country became engaged in a determined effort for their right to vote. The London National Society for Women’s Suffrage (LNSWS) initiated one of the early campaigns. Augusta was one of the 1,521 signatures on the first petition for women’s suffrage which was presented to Parliament by Augusta’s City of Westminster MP John Stuart Mill on 7th June 1866 28. Because it was so controversial, the petition was said to have been hidden under the stall of an apple seller for Mr Mill to collect.

Augusta joined the LNSWS the following year with the group holding annual meetings discussing how their campaign could progress. However, it would be another 52 years before the 1918 Representation of the People Act was passed to enable some women over the age of 30 to vote, before all women over 21 were given the right to vote in 1928 29.

Moving to Shere

Although Augusta and Rosa were living in London, they were spending time with their widowed mother at Drydown House as well. In September 1866, Augusta, along with her mother and sister-in-law, took part in a charity concert held at Shere Girls’ School for ‘the benefit of women of Shere, above 70 years of age’ 30. A notable addition to the concert was the conductor – Arthur S Sullivan, already well known as a composer but soon to find global fame for his light operatic works written with William S Gilbert 31.

Their mother Mary died at Drydown on 12th October 1870 aged 69 32. However, it seems that Augusta and Rosa didn’t immediately move there as the 1871 Census showed them living in Lower Grosvenor Square very close to Buckingham Palace in central London 33. Drydown, still under the ownership of their brother, was being looked after by the gardener, his wife the cook, and a servant 34, 35.

However, Augusta and Rosa were making their mark in Shere. In 1870, they had helped fund the building of a School Room in Peaslake, a village just to the south of Shere 36. In June 1873, they hosted a cricket match between the Shere Choral Society and a team of Shere villagers 37. Lunch for the players and their wives, a tea at Drydown following the match plus games and singing were all laid on by Augusta and Rosa, their ‘liberality had provided the whole day’s entertainment’.

Education continued to be at the forefront of Augusta’s interests. In 1876, she was involved in the refurbishment of Shere School’s reading room but was also helping other local concerns 38. Along with Rosa, they staged a concert in Shere for the benefit of the Surrey County Hospital 39.

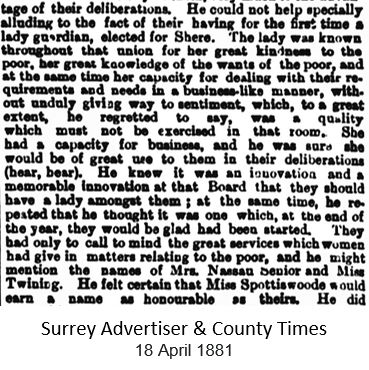

First woman elected to Guildford Board of Guardians

Augusta’s philanthropic attitude and energy in and around Shere brought her to the attention of the Guildford Union Workhouse Board of Guardians and in April 1881, at the age of 57, Augusta became the first woman to be appointed onto the Board 40. Chairman Mr EJ Halsey said Augusta, who would be representing Shere in her role, was ‘known throughout that union for her great kindness to the poor, her great knowledge of the wants of the poor and at the same time her capacity for dealing with their requirements and needs in a business-like manner, without unduly giving way to sentiment …. She had a capacity for business, and he was sure she would be of great use to them’ 40.

Augusta’s philanthropic attitude and energy in and around Shere brought her to the attention of the Guildford Union Workhouse Board of Guardians and in April 1881, at the age of 57, Augusta became the first woman to be appointed onto the Board 40. Chairman Mr EJ Halsey said Augusta, who would be representing Shere in her role, was ‘known throughout that union for her great kindness to the poor, her great knowledge of the wants of the poor and at the same time her capacity for dealing with their requirements and needs in a business-like manner, without unduly giving way to sentiment …. She had a capacity for business, and he was sure she would be of great use to them’ 40.

One of her first appointments, to be a member of the School Attendance Committee, was announced by the Board that same day. She certainly did this enthusiastically, for example spending many days at Peaslake School which she had helped found back in 1870 41.

A New Life in Canada – Emigration of Orphans and Paupers to Canada

During her time on the Board of Guardians, Augusta championed the emigration of orphans and pauper children to Canada, believing that this would afford them better opportunities in their lives. Child migration schemes were already in place in England including that run by John T. Middlemore who, from his base in Birmingham, had since 1873 been taking disadvantaged children from around the country to a receiving home in London, Ontario, from where the children would be sent to live with and work for a suitable family 42.

Augusta brought this idea to the attention of the Board of Guardians, and in early 1883, it was decided that they should join the scheme 43. Chairman Mr EJ Halsey said that he ‘knew from personal observation in Canada that the children were exceedingly well looked after and much sought for’ but admitted that ‘It was an experiment on the part of the Board, but it had been thoroughly well thought out’. Purely pragmatic financial reasons were also behind the Board’s decision. The cost of feeding, clothing and educating a child in the Workhouse was 3 shillings per week, equal to £7 10s per year (15p/£7.50), with the cost of emigration paying for itself within 18 months.

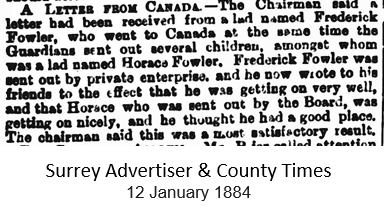

Eventually, four children were chosen by the Board to be sent to Mr Middlemore’s Guthrie House base in London, Ontario. On 7th June 1883, two pairs of siblings, Frederick and Horace Fowler plus Alice and James Hart were among 125 children from around the country on board SS Circassian in Liverpool, bound for Quebec. The scheme obviously had good intentions – for 11-year-old Alice and James, 9, their background was ‘Mother dead and Father has deserted them for more than 3 years and is a very bad character’ – but the siblings would be sent to different homes in Canada and separated from their older brothers.

Four months later, Augusta defended the Board’s decision to send children to Canada, writing a paper entitled ‘Bringing Up of Workhouse Children’ which was presented at a regional Poor Law Conference in London 44. In it, Augusta said: ‘The openings for children, and especially girls, are much more advantageous than in this country; and in many cases it is good for the children to be taken out of the way of relations, who often wish to regain a hold on them as they become of an age to earn money’.

Augusta would certainly have been delighted when she received in November 1884 an ‘affectionate and cheering letter’ from Alice Hart from her new family home in Ontario 45. A similar letter had also been sent to the Board of Guardians about Frederick and Horace Fowler 46.

Augusta would certainly have been delighted when she received in November 1884 an ‘affectionate and cheering letter’ from Alice Hart from her new family home in Ontario 45. A similar letter had also been sent to the Board of Guardians about Frederick and Horace Fowler 46.

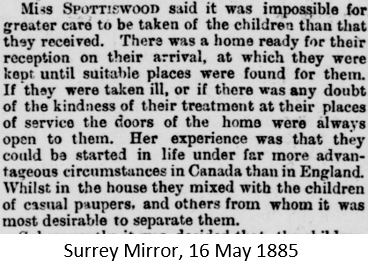

These letters did not stop strong opposition amongst the Board of Guardians to Augusta’s plans to send a small number of children to Canada under the scheme each year. At a heated meeting in May 1885, Board member Aaron Wells said that he was ‘strongly averse’ to sending the children, and that ‘if the Board would have them called in, and saw for themselves how small and helpless they were, they would feel the same aversion to sending them so far away’ 47.

Augusta responded by reminding the Board about the ‘letters of satisfaction’ they had received from previous emigrants, but another Board member, Thomas White, supported Aaron Wells, saying that a Godalming girl from a Dr Barnado’s home in London had recently been sent to Canada without the Guildford Union Board obtaining the permission of her grandmother. When the woman had saved some money to travel to see her granddaughter at the home, she was extremely upset to find that her granddaughter had been sent to Canada three months earlier.

Augusta did receive some support from other Board members, including Reverend Dr Haig Brown who believed that ‘the opportunities for the children to help themselves was far greater there than here’. Augusta went on to say that it was ‘impossible for greater care to be taken of the children than that they received’.

Augusta did receive some support from other Board members, including Reverend Dr Haig Brown who believed that ‘the opportunities for the children to help themselves was far greater there than here’. Augusta went on to say that it was ‘impossible for greater care to be taken of the children than that they received’.

The Board finally decided to call into the meeting the nine children that had been chosen to emigrate to Canada the following month. Aged between about 12 and 3 years old, they were asked if they were willing to travel, with the eldest saying they were. The Board then voted on what should be done, and it was carried by four votes that the six eldest should travel, with the three youngest remaining in the Workhouse.

However, the matter was still not resolved as the Local Government Board refused to sanction the emigration of 3-year-old Ada Walker, the youngest of three siblings intended for travel, because of her ‘tender years’ 48. At the Board meeting four weeks later, a letter from their uncle Frederick Walker was read out in which he said that he would look after Ada if the Board would offer him a ‘little assistance’. Board member Aaron Wells, who was staunchly opposed to Augusta’s ideals of sending children to Canada, said that he felt Workhouse was still the best place for Ada. After the means of Ada’s uncle Frederick Walker were found to be insufficient, it was decided that she would remain in the Workhouse while her two siblings Ann and John Walker, plus the three other children, Walter Shires, Alfred Curtis and Elizabeth Hall, would travel to Canada.

Walter, the eldest of the six children at 12 years old who had almost certainly been one those who had stood in front of the Board to give his agreement to emigration, took time to settle in Canada. An early report from when he was living on a farm in Chatsworth, Ontario said that Walter was ‘honest, untruthful, stubborn and sulky, and a great source of trouble’ but was ‘showing signs of improvement’. Fortunately, the latter proved to be the case, with Walter going on to spend the rest of his life in Canada 49.

Two years later in 1887, Ada Walker, now 5 years old, was now deemed old enough to travel to Canada with five other children 50. With them was former Workhouse inmate 18-year-old Rose Hebburn, accompanying her younger sisters Ellen and Eliza on the voyage. Five years earlier, Rose had gone into service for a widow in Pirbright arranged by the Guildford Board of Guardians, but Rose had fallen pregnant in early 1886 51. Although no record has been traced about the fate of the unborn child, Rose was taken in by Augusta, giving Drydown as her home address on emigration 52.

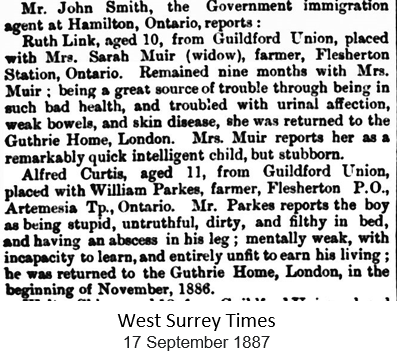

The Guildford Union Board was kept informed by the Canadian authorities of the progress of the children sent by them 53. Not all placements were successful. One child was reported to be ‘a great source of trouble as being in such bad health’ and so was returned to the Guthrie Home 1887. Another child was found to be ‘mentally weak … entirely unfit to earn his living’.

The Guildford Union Board was kept informed by the Canadian authorities of the progress of the children sent by them 53. Not all placements were successful. One child was reported to be ‘a great source of trouble as being in such bad health’ and so was returned to the Guthrie Home 1887. Another child was found to be ‘mentally weak … entirely unfit to earn his living’.

In the light of such reports, the Canadian Government, whilst recognising that the scheme was in general successful, called out specifically the Guildford Union and the Liverpool Union, for sending clearly ‘unfit’ children, contrary to Canada’s conditions for acceptance of orphan children. The Canadian Government stated that ‘The offending Boards of Guardians should at the same time be made clearly to understand that the conditions under which orphan children are now allowed to proceed to Canada must be strictly adhered to’ 54.

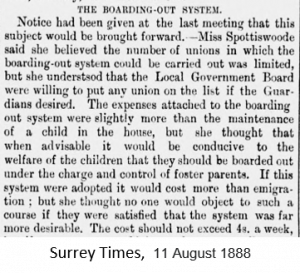

Despite this, Augusta continued to support the project, which saw over 100,000 children emigrated to Canada from the UK, throughout her time on the Board of Guardians. 55. She also became an advocate for ‘Boarding Out’ of workhouse children to local foster parents at the expense of the Union as it would be ‘conducive to the welfare of the children’. Augusta presented her research and proposal to the Board, and the scheme was agreed for the small number of suitable Workhouse children 56.

Despite this, Augusta continued to support the project, which saw over 100,000 children emigrated to Canada from the UK, throughout her time on the Board of Guardians. 55. She also became an advocate for ‘Boarding Out’ of workhouse children to local foster parents at the expense of the Union as it would be ‘conducive to the welfare of the children’. Augusta presented her research and proposal to the Board, and the scheme was agreed for the small number of suitable Workhouse children 56.

Other achievements in the Workhouse

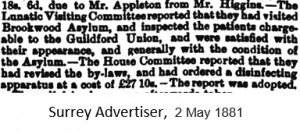

Augusta was involved with many other committees during her time on the Board, including those for ‘House and Land’ (upkeep of Workhouse buildings and estate) and  ‘Lunatic Visiting’ 57. The latter involved regular visits to the nearby Brookwood Asylum to monitor that Guildford Union patients who had been deemed unsuitable to live in the Workhouse were being well cared for.

‘Lunatic Visiting’ 57. The latter involved regular visits to the nearby Brookwood Asylum to monitor that Guildford Union patients who had been deemed unsuitable to live in the Workhouse were being well cared for.

Augusta was sensitive to the fact that being an inmate of the Workhouse carried a social stigma, so she was behind the abolition of uniform clothing for inmates, so that they were not conspicuous when seen outside of the Workhouse 88.

Life outside the Guildford Union

The Guildford Union Board of Guardians met every two weeks, leaving plenty of time for Augusta and her sister Rosa to pursue their own projects in Shere and the surrounding villages. They owned a number of properties in Shere and Peaslake which they rented out – but with very strict rules. One of those was that any boys in the family, must have separate downstairs bedrooms 36. They also warned their tenants that if any unmarried girl gave birth, her family would be turned out.

Augusta and Rosa’s rules were no doubt based upon them being staunch churchwomen and patrons of the Church of England Temperance Society who saw alcohol as the devil 58. This attitude brought about some good for Shere when the sisters allegedly decided that visitors to  the village’s White Horse Inn should have an alternative ‘local drink’ and thought water was a good option 59. So, in 1886 they paid for the sinking of a well to draw pure water up to a drinking fountain installed opposite the Post Office in Middle Street. One of the first committees Augusta had sat on as a Guardian in 1881 was the Guildford Rural Sanitary Authority which looked at the growing problem of pollution in the area, caused by local industries such as tanning and poor sewage removal 60. Maybe Augusta’s intention was to ensure safe, clean water in the village, and not just to keep the locals sober!

the village’s White Horse Inn should have an alternative ‘local drink’ and thought water was a good option 59. So, in 1886 they paid for the sinking of a well to draw pure water up to a drinking fountain installed opposite the Post Office in Middle Street. One of the first committees Augusta had sat on as a Guardian in 1881 was the Guildford Rural Sanitary Authority which looked at the growing problem of pollution in the area, caused by local industries such as tanning and poor sewage removal 60. Maybe Augusta’s intention was to ensure safe, clean water in the village, and not just to keep the locals sober!

Augusta and Rosa certainly made the Temperance Society strong in their area, as about 200 members from Shere, Peaslake and Albury were taken by train to Portsmouth and Southsea for a day trip in July 1890 arranged by them 61.

The religious beliefs of Augusta and Rosa had led to the School Room in Peaslake, which they had helped fund back in 1870, being used for Sunday church services 62. By 1888, however, it was deemed insufficient for this purpose, so it was decided that a church was required in the village. With Augusta and Rosa again helping with the funding, they were given the honour of laying the foundation stone in September 1888 for St Mark’s Church. Augusta and Rosa also provided the organ for the Church which held its first service in April 1889, followed by tea for over 300 Peaslake inhabitants, courtesy again of the sisters.

The religious beliefs of Augusta and Rosa had led to the School Room in Peaslake, which they had helped fund back in 1870, being used for Sunday church services 62. By 1888, however, it was deemed insufficient for this purpose, so it was decided that a church was required in the village. With Augusta and Rosa again helping with the funding, they were given the honour of laying the foundation stone in September 1888 for St Mark’s Church. Augusta and Rosa also provided the organ for the Church which held its first service in April 1889, followed by tea for over 300 Peaslake inhabitants, courtesy again of the sisters.

Local politics

The Local Government Act of 1894 saw the establishment across the country of local councils, including the Guildford Rural District and Shere Parish Councils with Augusta becoming a councillor for both 63.

The first meeting of the Guildford Rural District Council was held in the Workhouse Boardroom on 30th December 1894 with Augusta made part of the ‘Pollution of Tillingbourne and Provision of Sewers Committee’ 64. This continued her work that she had been doing with the Rural Sanitary Authority to tackle this issue.

Four days later, Augusta was at the first Shere Parish Council meeting held in the School Room, although she was only a councillor for them for one year 65.

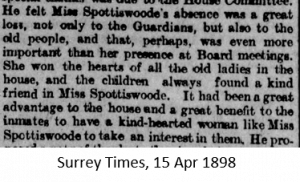

Augusta retires, death of Rosa

In early 1898, 74-year-old Augusta retired after nearly 17 years’ service with the Guildford Union Workhouse Board of Guardians and four years on the Guildford Rural District Council, so that  she could nurse her sister Rosa who was suffering from heart disease. The Chairman of the Board of Guardians paid tribute to her, saying ‘She won the hearts of all the old ladies in the (work)house, and the children always found a kind friend in Miss Spottiswoode’ 66.

she could nurse her sister Rosa who was suffering from heart disease. The Chairman of the Board of Guardians paid tribute to her, saying ‘She won the hearts of all the old ladies in the (work)house, and the children always found a kind friend in Miss Spottiswoode’ 66.

On 22nd April that year, Rosa passed away at Drydown aged 76 with the funeral held at Shere Church 67, 68. Augusta’s brother George was among the mourners, but he died the following year leaving Augusta as the only surviving sibling 69, 70. Her other brother William, a renowned mathematician and scientist, had died in 1883 and was interred in Westminster Abbey 20.

Despite the loss of Rosa, Augusta was intent in carrying on with her charitable work. She wrote to the Guildford Board of Guardians requesting to take inmates for their annual visit to her Drydown home on Whit Monday, so on 23rd May, just 31 days since Rosa’s death, Augusta welcomed more inmates to her home for the day 71.

In September 1898, to mark her retirement, Augusta was presented by the Guildford Board of Guardians with an inkstand 72. Mr EJ Halsey, who was Chairman of the Board when Augusta was appointed in 1881, said she joined when ‘but few, if any, women of the country had done so.’ Her appointment had been of marked benefit to the Guildford Union. She had always been ‘faithful to the ratepayers’ interests’ showing ‘unvarying sympathy to the inmates of the workhouse’.

Final years

Augusta was now alone at Drydown, although the 1901 Census showed that this was not strictly true because of the number of residential staff she employed 73. There was a lady’s maid, a butler who at 76 was just a year younger than Augusta, a cook, two housemaids, a kitchen maid and a houseboy. Three of her staff were only 14 years old with at least one of them, housemaid Louisa Riddick, from the Guildford Union Workhouse 74.  During her time on the Board of Guardians, Augusta had supported girls’ training in domestic duties as well as arranging placements for boys, including those with disabilities, to help them gain employment in later life 75, 76.

During her time on the Board of Guardians, Augusta had supported girls’ training in domestic duties as well as arranging placements for boys, including those with disabilities, to help them gain employment in later life 75, 76.

The day after the Census, Augusta demonstrated that it was not just people that she cared for as she presided over the annual meeting of the Guildford branch of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 77.

Augusta remained a supporter of many charities, including for famine refugees in India and families of soldiers that served in the Boer War 78, 79.

Despite her advancing age, Augusta continued to invite Guildford Union Workhouse inmates to Drydown on Whit Mondays. In 1907, 130 people enjoyed her hospitality of games, tea, musical entertainment and gifts 80.

At the time of the 1911 Census, Augusta was 87, living on ‘Private means’ at Drydown 81. She had devoted staff – her lady’s maid, 76-year-old Mary Ann King Fortt, and cook, Eliza Seaker aged 67, had both been with Augusta for over thirty years. Augusta now had a ‘sick nurse’ as well as five more staff including three teenagers who had been Guildford Union Workhouse inmates 82, 83.

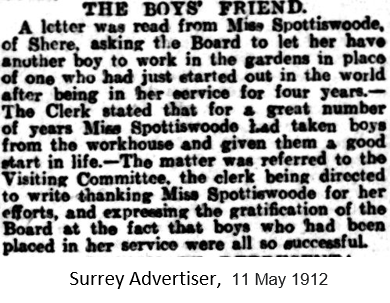

In May 1912, Augusta requested the Guildford Union Workhouse for a boy to replace the one who had been working for her as a gardener and houseboy for the previous four years 84. She was now in failing health, but this was not her last correspondence with the Workhouse Board of Guardians as later that month, she offered once again to ‘entertain the old people on Whit Monday’ at her Drydown home, which the Board accepted with thanks 85.

Death of Miss Augusta Spottiswoode

It is not known if this event did take place, but just over two months later, on 3rd August 1912, Augusta passed away at Drydown, aged 88, from ‘decay of nature’ 86.

Her funeral took place five days later at Shere’s St James’ Church which was attended by family, friends, associates and many more from all walks of life 87, 88. Her coffin was borne by seven of her tenants from the many local homes that she owned, while her grave was decorated with flowers by her gardener 89.

Her funeral took place five days later at Shere’s St James’ Church which was attended by family, friends, associates and many more from all walks of life 87, 88. Her coffin was borne by seven of her tenants from the many local homes that she owned, while her grave was decorated with flowers by her gardener 89.

The Surrey Times noted many of her achievements during her ‘long life of social service’, summing up her lifetime of helping so many others to have a better life by saying: ‘Her many acts of kindness to children caused many people to truly term her “the children’s friend”’.

August 2025

Editor: Mike Brock

Spike Lives is a Heritage project that chronicles the lives of inmates, staff and the Board of Guardians of the Guildford Union Workhouse at the time of the 1881 Census. The Spike Heritage Museum in Guildford offers guided tours which present a unique opportunity to discover what life was like in the Casual/Vagrant ward of a Workhouse. More information can be found here

Spike Lives is a Heritage project that chronicles the lives of inmates, staff and the Board of Guardians of the Guildford Union Workhouse at the time of the 1881 Census. The Spike Heritage Museum in Guildford offers guided tours which present a unique opportunity to discover what life was like in the Casual/Vagrant ward of a Workhouse. More information can be found here

References

The primary source of information was the Guildford Union Board of Guardians Minute Books, held at the Surrey History Centre, Woking, references BG6/11/20-28. Board of Guardian meetings were also reported extensively in the newspapers of the day, and references to representative articles are given below, sourced through The British Newspaper Archive. Ancestry.co.uk was used for official parish and census records. A complete list of references is here: Augusta Spottiswoode References