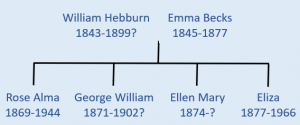

Rose, George, Ellen and Eliza Hebburn

Subject Names: Rose Hebburn (b1869 – d1944)

George Hebburn (b1871 – d1902?)

Ellen Hebburn (b1874 – d?)

Eliza Hebburn (b1877 – d1966)

Researchers : Mike Brock and Carol Thompson

The shocking abandonment of seven children from two families in Guildford on 8 May 1880 caused a public outrage, but thanks to the efforts of the Guildford Union Workhouse Board of Guardians, there was to be a brighter future for at least three of the children after they had experienced such neglect and despair.

The guilty parents were William Hebburn and Catherine Jackman who, after running away together, were to evade the authorities until October 1883. On that fateful day in 1880, widower William’s children were Rose age 10, George 8, Ellen 5 and Eliza 3, while Catherine’s abandoned children were Flora 9, George 8 and Grace 3.

The children of course were the innocent victims. This account tells the story of the Hebburn children.

1868 – 1877 : Growing up around Guildford

Rose Alma Hebburn was born on 19 April 1869 at Woodbridge Hill, Guildford, the first child of 23-year-old Emma Hebburn nee Becks, and William, 26, a labourer. Emma and William had married in nearby Worplesdon on 6 December 1868, so Emma would have been pregnant at that time.

Rose Alma Hebburn was born on 19 April 1869 at Woodbridge Hill, Guildford, the first child of 23-year-old Emma Hebburn nee Becks, and William, 26, a labourer. Emma and William had married in nearby Worplesdon on 6 December 1868, so Emma would have been pregnant at that time.

Less than two months after Rose’s birth, William served 21 days in Wandsworth Prison after being found guilty of assault. He was arrested again in December 1869 for poaching, being sentenced to a further six months in Wandsworth Prison.

The 1871 Census showed the three of them reunited at Woodbridge Hill with William noted as a labourer. Emma was expecting their second child, George William, who was born there on 15 August.

Emma and William’s third child Ellen Mary was born on 23 August 1874 at 13 Point Pleasant, Wandsworth, very close to the south bank of the River Thames and – maybe significantly – just a short walk from Wandsworth Prison.

Their fourth and final child Eliza was born on 27 March 1877 in Richmond Union Workhouse. The family were now residing in Mortlake, just a short distance from Richmond, and all the family, excluding William, had gone into the Workhouse just over a month earlier on 23 February. Rose, now 7, and George, 5, were moved to a District School on 16 March while Ellen, or Mary as she was then known, was not yet 2 so she remained with her mother.

The day after Eliza was born, William joined his family in the workhouse, remaining there for a month before he left on 28 April. A week later, on 5 May, he returned to collect Emma, Mary and Eliza. There are no records of Rose and George leaving the District School at this time.

Sadly, things were about to turn much worse for the four children as just a few months later, their mother Emma was struck down with a fever and died, age just 34, on 4 November 1877 in Bellfields, just to the north of Guildford. She was buried five days later in an unmarked grave at St John’s Church, Stoke-next-Guildford.

William appeared to still be with his family as he was noted on Emma’s death certificate as the witness, but now he was in the unenviable position of having four children under the age of eight to care for while trying to earn a wage. No records have been found to indicate that he had been in further trouble with the police since his imprisonment seven years earlier, but he was clearly in a difficult situation and almost certainly would have wanted to marry again.

William Hebburn and Catherine Jackman

The woman who was to become William’s partner in crime, Catherine Jackman, was living just a couple of miles away in central Guildford. Born in east London in 1848 as Clio Catherine Freeland, she had married 23-year-old Jerry (Jeremiah) Jackman in Guildford in 1868. They soon had two daughters, Clio Catherine in 1868 and Flora Annie in 1869, but things started to go wrong as in February the following year, Jerry was sent to Wandsworth Prison for 21 days with hard labour for “leaving his wife and children chargeable to the Guildford Union” the previous summer.

Jerry was in Wandsworth Prison again in September 1870 for 21 days, and then served four months more in 1871 for stealing a ham in Worplesdon.

Their third child, George, was born in 1873, but the relationship between Catherine and Jerry was becoming ever more troubled. Catherine, age 28, gave birth for a fourth time on 9 October 1876, this time in the Guildford Union Workhouse, to a daughter, Grace Maud. Catherine stated on the birth certificate that she was a widow, and no father was named. Revelations at Catherine and William Hebburn’s trial seven years later showed that Catherine had not been telling the truth and that husband Jeremiah was still alive, although the identity of Grace’s father has remained unknown.

There is no record to show exactly when and how William and Catherine first came to be together. They certainly knew each other by early 1880. Newspaper reports on the duo’s trial in October 1883 stated that Catherine had been convicted on 18 February 1880 for deserting her children after she and William had been apprehended by a policeman in the London Road as they were heading out of Guildford. While Catherine served her 21-day sentence in 1880, her four children were taken into the Guildford Union, with the one report saying “they were alive with vermin”. It appears that William was not brought to trial at that time, and it is not known where his children were then.

It was not long before William and Catherine attempted to disappear again, and this time they were somewhat more successful. The newspaper reports on their subsequent capture and trial in 1883 said that William and Catherine had left seven children on 8 May 1880 with Catherine’s 60-year-old widowed mother, Ann Luxon, in Chertsey Street, Guildford before doing their vanishing act. The relieving officer for the Guildford Union confirmed at the trial that seven children (Rose, George, Ellen and Eliza Hebburn; Flora, George and Grace Jackman) had become “chargeable to the Union” from that date, which meant they had been taken there to live. Catherine’s oldest daughter, 12-year-old Clio Catherine, now known as Kate, was almost certainly living with Catherine’s mother at this time, as they are noted at the same address in Guildford in the 1881 Census.

Not surprisingly, there are no records to indicate where William and Catherine had gone, but it seems clear that Catherine’s estranged husband Jerry was at least partially aware of what had happened. Catherine’s mother Ann stated at the trial in 1883 that she had briefly spoken with Jerry shortly after the children had been admitted to the Union in 1880. “Oh, mother!” he had said to her before running away.

Sadly, Catherine’s youngest daughter Grace passed away in the Workhouse in March 1881, age just four. Ann was obviously upset about the death of her grand-daughter, and a few weeks later on 18 April, she waited outside the Stoke Schools until Flora and George appeared, and took them home with her, thereby removing them from the Guildford Union’s care, at least temporarily. Read what happened to Flora and George Jackman here.

The four Hebburn children remained in the Workhouse with seemingly no one on the outside having an interest in their lives. When Rose reached the school leaving age of 13 in April 1882, she left the Workhouse to go into service as a maid in the nearby village of Pirbright, although she was still under the supervision of the Guildford Union.

From May 1880, the police had been searching for William and Catherine, but had no success until September 1883 when both were discovered in a dramatic scene at Catherine’s mother Ann’s house in Guildford. One local newspaper reported that Catherine had returned to her mother, not with William, but with an illegitimate child fathered by William. The authorities were unaware that Catherine had returned until on Saturday 29 September 1883, the police were called to a disturbance at Ann’s home where they found William clashing with Catherine over the custody of the 15-month-old child. It was said that William had the child’s clothing in his teeth as he tried to wrest the child from Catherine’s grasp, until a crowd, including militiamen, separated them. When Police Sergeant Titley arrived on the scene, he recognised William as the man he had been looking for during the past three years. William said to Titley that he had intended to give himself up, and as he was marched through Guildford to the police station, a hostile crowd gathered around them, clearly incensed by William’s behaviour.

The trial took place just two days later on Monday 1 October 1883, with the Borough Bench sentencing William and Catherine to three months hard labour each. The Mayor described their conduct as “disgraceful”.

William’s whereabouts are unclear after completing his prison sentence in early 1884. It seems most likely that he was the William Hebborn imprisoned for six months in Wandsworth in March 1898 for begging, after a string of similar offences. The UK Calendar of Prisoners noted him as an “incorrigible rogue” which would seem to be a fitting description for his adult life. William died a few months later in January 1899 in the Battersea Union Infirmary.

Hebburn children in the Workhouse

It is hard to imagine what the impact of being dumped back in 1880 would have been on the children. For William’s four children, the fact that their father had re-appeared over three years later in 1883 did not change their lives. William was in no position to be responsible for them so, George now 12, Ellen 9 and Eliza 6, remained in the Guildford Union. Rose, 14, was still employed as a live-in servant for a widow in Pirbright. We do not know if the children ever saw their father again.

George would probably have left the Workhouse in August 1884 on his 13th birthday ready for employment. The 1891 Census showed him living in nearby Worplesdon working as a servant for a farmer.

By the Autumn of 1886, 17-year-old Rose had been working as a servant for well over four years, but this came to an end when she fell pregnant. She was taken back to the Guildford Union Workhouse, with the Board of Guardians considering whether to take any action against her employer and guardian, but they eventually decided to await the birth before deciding what to do. No record of a birth or any further report from the Board of Guardians has been found, so it seems most likely that Rose lost her child during the pregnancy.

May 1887 marked the seventh year Ellen, now age 12 and Eliza, 10, had lived in the Workhouse since being abandoned by their father, but their lives were about to take a dramatic turn.

Canada

On 21 May 1887, a meeting of the Board of Guardians of the Guildford Union Workhouse announced that “they were prepared to assent to the Emigration of Orphans and deserted pauper children to Canada”. Nine children aged between five and 12 had been selected to travel, which included Ellen and Eliza.

The driving force behind this initiative was Miss Augusta Spottiswoode, the only woman on the Board of Guardians for the Guildford Union. She was independently wealthy, influential, and clearly a strong-minded and forward-thinking person as she had signed the first petition for women’s suffrage presented to parliament in 1866.

The annual emigration of a selection of children from Guildford had begun in June 1883, when four children were sent to begin a new life in Canada. Not everyone on the Board of Guardians agreed that emigration was right for the children, but Miss Spottiswoode argued in 1885 that “they could be started in life under far more advantageous circumstances in Canada than in England”.

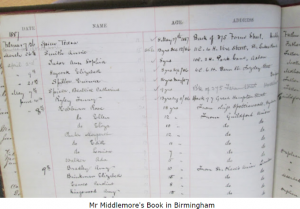

Miss Spottiswoode made the arrangements through the Children’s Emigration Home in St. Luke’s Road, Birmingham which was run by Mr John Throgmorton Middlemore. His organisation handled the emigration of children from all around the country including arranging placements for the children in Canada. He also oversaw training at his Birmingham base for the older children to enable them to work as domestic servants. Only children with the worst chances were accepted, and life for them in Canada was to be challenging in very many ways.

On 8 June 1887, Ellen and Eliza, along with four others from the Guildford Union – three less  than originally intended – arrived in Birmingham. They were also joined by their sister Rose. The record states that she had come from Miss Spottiswoode, so it would seem likely that since the loss of her child, 18-year-old Rose had been living at Miss Spottiswoode’s home at Drydown House, Shere.

than originally intended – arrived in Birmingham. They were also joined by their sister Rose. The record states that she had come from Miss Spottiswoode, so it would seem likely that since the loss of her child, 18-year-old Rose had been living at Miss Spottiswoode’s home at Drydown House, Shere.

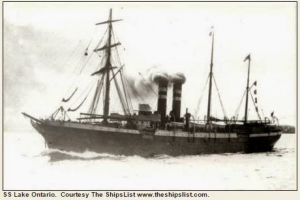

An estimated 140 children were given a send-off presided over by the Mayor of Birmingham at the Exchange Rooms, New Street. They were escorted the following day, 10 June 1887, on a train to Liverpool before boarding the Beaver Lines’ SS Lake Ontario for its maiden voyage.

An estimated 140 children were given a send-off presided over by the Mayor of Birmingham at the Exchange Rooms, New Street. They were escorted the following day, 10 June 1887, on a train to Liverpool before boarding the Beaver Lines’ SS Lake Ontario for its maiden voyage.

The ship arrived in Quebec, Canada on 18 June, with the three sisters moving on to Guthrie Home, Middlemore’s receiving house, in London, Ontario.

The ship arrived in Quebec, Canada on 18 June, with the three sisters moving on to Guthrie Home, Middlemore’s receiving house, in London, Ontario.

Rose, Ellen and Eliza were among the 2,200 young adults and children who passed through Guthrie Home after it opened in 1873.

Rose Alma

The first record of Rose moving on from Guthrie Home was six months later on 22 December 1887, when she was assigned to work for Mr ANC Black in Dutton, about 30 miles (50km) south-west of London, Ontario.

The first record of Rose moving on from Guthrie Home was six months later on 22 December 1887, when she was assigned to work for Mr ANC Black in Dutton, about 30 miles (50km) south-west of London, Ontario.

How long she remained there is not known, but less than three years later, on 1 September 1890 Rose married James Collins in North Tonawanda, just over the United States border close to Niagara Falls, about 160 miles east of Dutton.

The Niagara Falls area on the US side had become highly industrialised by this time, offering many skilled and unskilled work opportunities in its factories and mills. However historians note that it was not a nice place to live in the 1890s, blighted by heavy pollution, shanty towns, poverty and crime.

The Niagara Falls area on the US side had become highly industrialised by this time, offering many skilled and unskilled work opportunities in its factories and mills. However historians note that it was not a nice place to live in the 1890s, blighted by heavy pollution, shanty towns, poverty and crime.

Rose and James had a son, Francis Lawrence Collins on 27 June 1891, with the 1892 New York State Census showing them living in Wheatfield Town, Niagara – James a 32-year-old watchman, Rose a housekeeper age 24, and one-year-old Francis.

Rose and James next appear on the 1900 US Census, and after navigating around the poor official entry which names them as “Collence” and says that Francis is their daughter, they are seen to have three more children – Lily, age 6, James 3 and Veronica 1. 39-year-old James was noted as a day labourer, although worryingly, it indicated that he had been out of work for 9 months in that year. Rose, now 32, is not noted as being in employment, so payment on their rented home must have been a problem. A fifth child, Vincent, was born in 1901.

Rose’s husband James died on 20 February 1903 from typhoid fever. Despite this terrible blow, 34-year-old Rose remarried within five months to English-Canadian John A Clarkson, on 3 July 1903. Their first child, registered as John Clarkson, was born on 16 July 1904, but even this early in their marriage, there was trouble brewing for Rose and the children. On 10 January 1905, Lily age 11, Veronica 7, Vincent 4 and Lawrence (John) 4 months were admitted to the Niagara County “Home for the Friendless” poorhouse in Lockport, with “father’s desertion” noted as the reason. They were released the same day. Rose’s son James age 9 seems to have been sent there on 7 February for the same reason, again just for the day, but perhaps more likely is that this is a clerical error and that it was actually 10 January, the same date as his siblings.

In 1903, before her second marriage, Rose Collins, “widow of James”, had been living at 927 Grove Avenue, in the City of Niagara Falls, just a short walk from the Falls. This directory noted four different addresses for John Clarkson, and presumably Rose and children, in the same area over the next five years. There may well have been more, and by the 1910 US Census, the family was living at 2328 Whirlpool Street, right next to the Niagara River which forms the boundary with Canada. John, 39, worked as a labourer in a soda factory, while Rose, 43, was at home with their three-year-old daughter Edna and the five children from her first marriage. What happened to Rose and John’s first child John/Lawrence is unclear. The Census states that Rose had had seven children of whom six were still alive, although no records have been found to confirm the child’s death.

The 1912 City directory showed a major change in the family’s circumstances with the entry naming Mrs R Clarkson at 1242 Center Avenue, and with no mention of John. Addresses change over the next two years but again John is not to be seen with his family before some clarification of the situation follows in the 1915 Census. It shows 47-year-old Rose living at 518 Ferry Avenue, Niagara Falls with five of her six children – Lily Collins, a 20-year-old waitress, James (18, salesman), Veronica (16, housework), Vincent (13, school) and Edna Clarkson (8, school), plus a lodger. In the Census, her husband John is boarding in nearby Fairfield Avenue, although the 1915 City Directory shows him to be a couple of blocks away from Rose at 710 Ferry Avenue. The directories for the next three years show him at this address too, so it seems clear that Rose and John were no longer living together.

In the 1920 US Census, John was still noted as living apart from his family, rooming with a married couple in Wheatfield, North Tonawanda, working as a labourer in a lumber yard. No records have been found for Rose and the rest of the family on this Census. The 1921 City Directory showed her to be at 935 Whirlpool Street, so the omission from the Census is likely to just be a clerical error or difficulty in reading faint entries.

John died in the Niagara Falls Memorial Hospital on 7 December 1923, age 53, following a bizarre incident in which he was struck on the head by a coffee cup two days beforehand, although the inquest found that his death was caused by natural causes and not from wounds caused by the cup.

Rose remained a widow for the rest of her life, staying close to her family. In 1925, she was living at 437 6th Street, Niagara, with her children James (28, pipe fitter), Vincent (23, car checker) and Edna (18, stenographer). She also had taken in two lodgers to give her some extra income.

By 1930 Rose had moved about 20 miles down the Niagara River to Buffalo City where she was living with daughter Lily and her husband August Wolf, and their daughter Edna. Rose was still living with them in Buffalo at the time of the 1940 Census. She passed away on 14 October 1944, age 75, in Tonawanda.

By 1930 Rose had moved about 20 miles down the Niagara River to Buffalo City where she was living with daughter Lily and her husband August Wolf, and their daughter Edna. Rose was still living with them in Buffalo at the time of the 1940 Census. She passed away on 14 October 1944, age 75, in Tonawanda.

Clearly keeping her family together was extremely important to Rose. Her story shows the grit and determination she must have had within her to achieve this, after the trials of her early life. The 1940 US Census notes that Rose had only completed the equivalent of Elementary School third grade, equivalent to age 8 or 9 nowadays. What an amazing lady!

Eliza (Elizabeth)

Rose’s youngest sister Eliza found her early years in Canada extremely tough. She had only ever known life in a workhouse and just two days after arriving in the country with her sisters Rose and Ellen, the 10-year-old was sent to the home of Mr SE Hooper in Clandeboye, just to the north of London, Ontario. Being separated from her sisters and living with a complete stranger must have been incredibly difficult for someone so young. Eliza moved on to another household in the area in May 1888, and then on Christmas Day 1888 she ended up at Almonte, near Ottawa, some 360 miles from her sister Rose in Dutton.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this poor child fell into deep trouble, being given a five-year sentence for larceny (theft) and was sent to the Andrew Mercer Reformatory / Industrial Refuge for Girls in Toronto on 19 February 1890. She was just 12 years old.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this poor child fell into deep trouble, being given a five-year sentence for larceny (theft) and was sent to the Andrew Mercer Reformatory / Industrial Refuge for Girls in Toronto on 19 February 1890. She was just 12 years old.

The institution had opened in 1880, and one of its aims was to re-educate the inmates in so-called “Victorian virtues”, including obedience and servility.

For Eliza, this seems to have marked a turning point in her life, as she was released for good conduct on 2 August 1892, having served less than 2 1/2 years of her sentence. No doubt the rigours and routine of an institution were very familiar to Eliza, making it easier for her to survive her punishment.

On release, Eliza must have headed very quickly to the United States to be near her sister Rose, as the next record dated 21 July 1894 shows Eliza, age 17, marrying Walter Isaiah Hilditch in North Tonawanda. Although noted on some records as English, Walter was born in 1868 in the Welsh village of Trewern, very close to the border with England.

For possibly the first time, Eliza now had some relative stability in her life, and by the time of the 1900 US Census, she had three children. Living in Fifth Avenue, North Tonawanda, 23-year-old Eliza was at home caring for Martha, 5, William, 3, and four-month-old Alfred, while husband Walter, 30, was a labourer.

Like Rose, life was not all plain sailing for Eliza, as the 1900 Census indicated that Walter had had four months out of work in the previous year. Another similarity in their lives was the frequency that the Hilditch family moved home. At one stage, in 1904, Eliza was living just a few doors away from Rose in the same street.

Directories additionally reveal that by 1910 Walter was no longer a labourer, but had found permanent work as an employee, in a house on Allen Avenue in Niagara Falls. The 1910 Census indicates that Walter is a watchman in a factory, and Eliza is now recorded as Elizabeth. Perhaps this name change was her way of distancing herself from her past?

Sadly, Walter passed away on 11 December 1912, age 44. Following the early loss of her husband, Elizabeth and her three children remained in Niagara. The 1915 US Census shows that Martha, 19, was helping her 37-year-old mother with the housework, while William, 17, was a book-keeper and 15-year-old Alfred, shown by his middle name of Edward, was a mail boy. The sons were doing well, but Elizabeth had taken in a lodger to help her finances.

In 1920 Elizabeth still lived with Martha and Alfred in Niagara, but at a new address with no lodger. Elizabeth and Alfred were both in work. Her son William had married Mabel Canavan in 1917, but remained living nearby in an owned home, which must have made his mother so proud. Her second son Alfred Edward married Ruth Shay in 1922, always remaining nearby in Niagara.

In 1920 Elizabeth still lived with Martha and Alfred in Niagara, but at a new address with no lodger. Elizabeth and Alfred were both in work. Her son William had married Mabel Canavan in 1917, but remained living nearby in an owned home, which must have made his mother so proud. Her second son Alfred Edward married Ruth Shay in 1922, always remaining nearby in Niagara.

The 1930 US Census shows Elizabeth and Martha living at 411 6th Street, Niagara, their home since before 1924, with two lodgers. Elizabeth was working as a domestic to a private family, Martha had no employment. In 1940, they had four lodgers living with them. Elizabeth, now 61, was employed as a matron at City comfort station, and Martha, 44, was “unable to work”.

After her daughter Martha passed away in 1946, Elizabeth continued to work, with the Niagara City Directory showing that until 1949 she was still employed as a cleaning superintendent despite being over 70 years old. She did finally retire and by 1954 had moved just over a mile north to live at 719 Linwood Avenue next to her son Alfred.

Elizabeth remained at Linwood Avenue until 16 November 1965 when she was admitted to Ransomville General Hospital where she passed away, age 89, on 30 August 1966.

The newspaper obituary noted that Elizabeth had been a member of the Women’s Benefit Association and a number of freemason lodges, so she had clearly been a highly respected member of the local community, a far cry from her early life. All this was in addition to caring for her own family and giving them a good start in life after being widowed so young, a clear indication of how far she had come through her own efforts. Again, an astonishing story of a Hebburn with strong character and true courage.

Ellen Mary

Less is known about the third Hebburn sister Ellen Mary. Like Eliza, she was very quickly moved on from Guthrie Home, going to live and work for Mr John H Elliott nearby just a week after she had arrived in Canada in June 1887. Ellen was still then only 12 years old.

Records indicate that Ellen worked for a number of different employers from 1887 to 1893. By 1892 she was clearly able to stand up for herself and not afraid to speak her mind, as one letter sent by her states that she left Mrs Ritchie’s employment “because the wages were not high enough”. Ellen was “anxious to have her sister’s address”.

A report from a Middlemore visitor from England written in September 1893 said that Ellen had left employment and had gone to Buffalo to be with her sister, though whether that was Rose or Eliza is not clear. That same report noted that Ellen “suffered a good deal from sore feet and was not able to do much for some time before she left”.

Unfortunately, we don’t know if Ellen reached her sisters, as no more records specific to her have been traced.

George William

Rose, Ellen and Eliza’s brother George William Hebburn did not travel to Canada with his sisters in 1887, as he was listed in the 1891 Census working in Worplesdon. No further trace of George has been found in English records, but there are passenger records that shows a “Geo Hebburn”, age 20, single, labourer, booked on a ship leaving Liverpool for Canada in late 1892.

Further evidence of the possibility of George leaving England is found in the Syracuse, New York State City Directory of 1895/96, which includes a “George Hepburn”. He was a coachman, a job that involves the caring of horses which is certainly a skill George William could have learnt back on the farm in Worplesdon. The listing was “George Hebbrun” in the 1896 Directory, and “George Helburn” in 1898, but all of them as a coachman. Syracuse is some 160 miles away from where Rose and Eliza were then.

The 1899 City Directory named him as “George W Hebburn”, listed under the heading “grocers”. The following year, the 1900 US Census showed Englishman George W Hebburn, age 29, living at 316 Putnam Street, Syracuse, New York State with his Irish wife Mary, 29, and their one-year-old daughter Florence. George was running a grocery store, although it said he had been unemployed for 11 months in the past year. The 1900 Syracuse Directory confirmed his name, occupation and address as the same.

The 1901 Syracuse Directory gave George as a grocer, now living at 125 Amy Street. The following year’s Directory said that George W Hebburn had passed away on 12 May 1902. He would have been just 30. Unfortunately, the full official death certificate has not been made available by the authorities, and no marriage registration has been found either, so it has not been possible so far to confirm categorically that this George was indeed the brother of Rose, Ellen and Eliza.

Final word

What the Hebburn children went through in the ten years following the death of their mother Emma in 1877, and quite possibly before that time too, is almost impossible to comprehend in the 21st century. It is clear, though, that the actions of the Guildford Union Board, most notably the kindness and generosity of Miss Augusta Spottiswoode at that time, gave Rose, Eliza and Ellen the chance to break out of their desperate situation and show what they could achieve.

The British Home Children in Canada website is an invaluable research resource for anyone interested in understanding more about the experiences and fate of these child emigrés.

September 2021

We are very grateful to Jim Littlewood (great grandson of Rose Alma Hebburn) and to Susan Mowry (partner of William James Hilditch Junior, great grandson of Eliza Hebburn) for their invaluable contributions to this story.

In memory of William James Hilditch Junior, 1945-2021.

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk and Ancestry.com

BritishHomeChildrenRegistry.com

CanadianBritishHomeChildren.weebly.com

General Register Office GRO.gov.uk

en.Wikipedia.org

Exploringsurreyspast.org

Findagrave.com

FindMyPast.co.uk (incl British Newspaper Archives)

Norwayheritage.com

Researchgate.net

Richmond Local Studies and Archive Library Richmond.gov.uk

Somerville66.blogspot.com

Surrey History Centre www.surreycc.gov.uk/culture-and-leisure/history-centre

Please click here for the annotated story

and here for the full list of references