MARY ANN JOYCE

and

WALTER SHIRES

Subject Names : Mary Ann Joyce (b1868 – d?)

Walter Shires (b1873 – d1937)

Researcher : Carol Gomm

Half-siblings Mary Ann Joyce, age twelve, and Walter Henry Shires, seven, were both in the Guildford Workhouse in 1881. But how did they come to be there? And what happened to them?

Mary Ann Joyce was born in Lyon’s Gate, High Street, Guildford on 20th July 1868 and baptised at St. Nicholas Church (spelt St Nicolas since the early 20th century), Bury Street, on the 6th December with her older brother William John (born 10th February 1867). They were the children of William, a farm labourer, and Kate Joyce, née May.

At the time of the 1871 Census, two-year-old Mary Ann and her family were living in St. Catherine’s, Artington, to the south of Guildford. Her parents were recorded as William, 25, an agricultural labourer born in Guildford, and Kate, 24, born in Stoke next Guildford. Mary Ann’s brother William John, four, was a scholar, and she now had a sister, Kate Elizabeth, nine months. Sadly, Kate Elizabeth died a few days after the Census and was buried at St. Nicholas Church on the 22nd April 1871.

Later that year, Herbert Edward was born, but tragedy struck the family twice in February 1872 with the deaths of Mary Ann’s father William age 26 on 10th February from ‘phthisis’ (tuberculosis), and baby Herbert twelve days later, age just six months. Both were buried at St. Nicholas.

Kate was not a widow for long as she married bachelor Walter Henry Shires, a labourer, at St. Nicholas on 27th April 1873. She was already expecting their first child who was born in Guildford on the 1st October and baptised at St Nicholas as Walter Henry ‘Sheires’ on 11th January 1874.

A second child, Edith Jane, was born in 1875 and baptised on 3rd September with the surname ‘Sheires’, but after the birth of Frank (‘Shiers’) in March 1878, the family’s situation took a dreadful turn. Frank died just a week later on 24th March from jaundice, and seven days after that, Kate also died, age 30, suffering from ‘phthisis’. She was buried on the 6th April at St. Nicholas.

This left Walter senior trying to earn a wage while having four children aged between  eleven and two – William, Mary Ann, Walter and Edith – to look after. This may well have been too much for him, and it seems likely that the family would have been forced to go into the Guildford Union Workhouse around this time. Although there are no admission records in existence to prove this happened, it is known from her burial record that Edith died in the Union, age three, in December 1878.

eleven and two – William, Mary Ann, Walter and Edith – to look after. This may well have been too much for him, and it seems likely that the family would have been forced to go into the Guildford Union Workhouse around this time. Although there are no admission records in existence to prove this happened, it is known from her burial record that Edith died in the Union, age three, in December 1878.

Less than four months later, on 17th April 1879, Walter senior died age 37 from heart disease in the Guildford Union and was buried on the 21st April at St. Nicholas, leaving William and Mary Ann from their mother’s first marriage, and Walter from her second, as orphans.

By the time of the 1881 Census two years later, William was 14 and employed as a farm labourer at Shalford, not far from where the family had been living in 1871.

Mary Ann, 12, and Walter, seven, were recorded as scholars in the Guildford Union, but this situation probably changed later that year when Mary Ann turned 13. When workhouse children reached this age, they were often sent out to work while remaining under the watchful eye of the Board of Guardians. This is most likely what had happened to William prior to the 1881 Census, while Mary Ann was likely to have been prepared for her departure that summer by being trained in housemaid and servant duties.

Desperate times for Mary Ann

Eight years later, however, Mary Ann’s life had hit rock bottom when a Guildford policeman  found her sleeping rough on the steps of the local newspaper office. The 1824 Vagrancy Act had made it illegal to beg or sleep rough, stating that ‘every person wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or waggon’ would be charged. Essentially, it criminalised homelessness.

found her sleeping rough on the steps of the local newspaper office. The 1824 Vagrancy Act had made it illegal to beg or sleep rough, stating that ‘every person wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or waggon’ would be charged. Essentially, it criminalised homelessness.

At her court appearance in May 1889, it was revealed that 21-year-old Mary Ann had no home and that she had been found in a similar situation in Guildford shortly before this incident when she had told a policeman ‘she was going to jump over a bridge’.

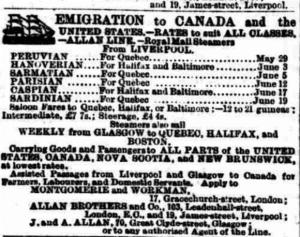

She also told him that she had been recently employed at the Napoleon Hotel in Guildford and  that she had lived in Canada for five years before that. This could mean that she had been one of the many thousands sent to Canada as part of the ‘British Home Children’ emigration programme which the Guildford Union Board were involved with. The Union began sending children to Canada in June 1883, but apart from a record showing the arrival in Canada of a ‘Mary Joyce’ in May 1884, no further records have been traced to show that this was her, so it is possible she had just invented the story. However, as she was at that time about 16, it is also possible that she herself had chosen to emigrate, perhaps under the ‘assisted passage’ scheme.

that she had lived in Canada for five years before that. This could mean that she had been one of the many thousands sent to Canada as part of the ‘British Home Children’ emigration programme which the Guildford Union Board were involved with. The Union began sending children to Canada in June 1883, but apart from a record showing the arrival in Canada of a ‘Mary Joyce’ in May 1884, no further records have been traced to show that this was her, so it is possible she had just invented the story. However, as she was at that time about 16, it is also possible that she herself had chosen to emigrate, perhaps under the ‘assisted passage’ scheme.

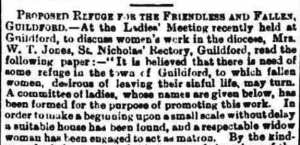

The result of Mary Ann’s Guildford court appearance was a sympathetic one, with a ‘Mrs Clark’  promising to take Mary Ann into a women’s refuge, and no charges would be brought against her – normally, a person would have faced up to one month in prison for vagrancy. The women’s refuge she was taken to was almost certainly the St Mary’s Refuge at 52 Chertsey Street, Guildford. Set up seven years earlier, its aim was to give shelter to ‘the friendless and fallen’ before moving the women to a Diocesan Home where they could be helped and rehabilitated.

promising to take Mary Ann into a women’s refuge, and no charges would be brought against her – normally, a person would have faced up to one month in prison for vagrancy. The women’s refuge she was taken to was almost certainly the St Mary’s Refuge at 52 Chertsey Street, Guildford. Set up seven years earlier, its aim was to give shelter to ‘the friendless and fallen’ before moving the women to a Diocesan Home where they could be helped and rehabilitated.

Despite these good intentions, it appears that Mary Ann’s life was about to follow an altogether different path. The 1891 Census showed her to be living in London at 14 Dorset Street, Spitalfields, an old four-storey property on the south side of the street. Age 22, Mary Ann was listed as single with ‘no occupation’, sharing a room with Anne E Brown, a 35-year-old spinster, also with no occupation. In the next room were two more unemployed single women, Helen Smith, 24, and 17-year-old Florence Butler. The rest of the property was shared by eleven people including four ‘married’ couples.

What the Census doesn’t say was that Dorset Street was one of the most notorious streets in London. Although only a little more than 100 metres long, it gained worldwide attention when the last and most violent of the Jack the Ripper murders, that of prostitute Mary Jane Kelly, took place on the 9th November 1888 at 13 Miller’s Court, situated in the former gardens of 26 and 27 Dorset Street. At the time of her murder, Mary Jane was renting it weekly with another prostitute. In fact, all six of the Ripper’s victims either lived or worked within walking distance of Dorset Street – another victim, Annie Chapman, frequented the lodging house at 35 Dorset Street.

Once a prosperous street lived in by Huguenot silk weavers, Dorset Street’s decaying buildings had been bought up cheaply in the 19th Century and almost entirely converted into  common lodging houses with large dormitories in which beds were let by the night, or houses with single rooms let on weekly terms. Taking advantage of the large number of men in the lodging houses – there were 180 in the lodging house at 9-10 Dorset Street in 1891, many of whom were casual workers at the docks – canny landlords installed prostitutes in their properties to provide them with a lucrative revenue stream. Men known as ‘bullies’ were employed to act as doormen to make sure no one came and went without paying. Some lodging houses catered for both men and women, with couples turning up to get a bed for the night claiming they were ‘married’ when in fact they were prostitute and client.

common lodging houses with large dormitories in which beds were let by the night, or houses with single rooms let on weekly terms. Taking advantage of the large number of men in the lodging houses – there were 180 in the lodging house at 9-10 Dorset Street in 1891, many of whom were casual workers at the docks – canny landlords installed prostitutes in their properties to provide them with a lucrative revenue stream. Men known as ‘bullies’ were employed to act as doormen to make sure no one came and went without paying. Some lodging houses catered for both men and women, with couples turning up to get a bed for the night claiming they were ‘married’ when in fact they were prostitute and client.

Charles Booth’s 1898 map of London Poverty showed Dorset Street coloured black, denoting the ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ among a sea of mostly pink which indicated moderate or mixed income. George Duckworth, who investigated the street for Booth, described it as ‘the worst street I have seen so far, thieves, prostitutes, bullies, all common lodging houses’.

‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ among a sea of mostly pink which indicated moderate or mixed income. George Duckworth, who investigated the street for Booth, described it as ‘the worst street I have seen so far, thieves, prostitutes, bullies, all common lodging houses’.

So what does all this say about Mary Ann’s situation at Number 14? How had she come to be there? Of course, not everyone living in the street was a criminal. Some inhabitants were honest but were there simply because they were so desperately poor and had nowhere else to go, barring the workhouse.

Whatever the truth was about Mary Ann’s situation, a few weeks after the 1891 Census, she married labourer Fergus O’Connor Helps at Christ Church, situated at the east end of Dorset Street, on the 29th June.

The marriage certificate is rather enigmatic as the true identity of Mary Ann’s husband is not  clear. No other record of a ‘Fergus O’Connor Helps’ has been found, but it seems possible that he was, or was purporting to be, Connor Helps, a 28-year-old single man from Leicester who had just completed a seven-year term with the 2nd Battalion Leicestershire Regiment in the British Army. Connor, a lance sergeant, had left the Army in London only four days before the wedding, but records indicate he had been with his unit at the Tower of London since 6th April 1891, just a short walk from Dorset Street. The banns for the marriage, which had been read in London on 14th, 21st and 28th June, gave the address for ‘Fergus O’Connor’ as ‘Tower’, presumably meaning The Tower of London.

clear. No other record of a ‘Fergus O’Connor Helps’ has been found, but it seems possible that he was, or was purporting to be, Connor Helps, a 28-year-old single man from Leicester who had just completed a seven-year term with the 2nd Battalion Leicestershire Regiment in the British Army. Connor, a lance sergeant, had left the Army in London only four days before the wedding, but records indicate he had been with his unit at the Tower of London since 6th April 1891, just a short walk from Dorset Street. The banns for the marriage, which had been read in London on 14th, 21st and 28th June, gave the address for ‘Fergus O’Connor’ as ‘Tower’, presumably meaning The Tower of London.

Sadly, the wedding is the last record traced for Mary Ann. At some stage, Connor returned to Leicester, where he passed away on 7th July 1895 in the Leicester Workhouse from malignant glandular disease and pneumonia, age just 31. No record was made on his workhouse entry or death certificate of his marital status, so it can only be speculated whether he was the actual husband of Mary Ann and, more importantly, what was the fate of Mary Ann herself.

A Fresh Start for Walter

Unlike his half-sister, Walter’s life was to take a very different turn.

In 1885, John Middlemore, the founder of the Children’s Emigration Homes scheme, had written to Guildford Union board member Miss Spottiswoode stating his intention to take children to Canada that June. At a meeting of the Guildford Union Board of Guardians on the 9th May 1885, it was noted that nine children in the Guildford workhouse were ‘eligible for emigration’, but only six were finally selected, including ’Walter Shiers (12)’, actually only 11 years old.

All of them appeared to go voluntarily. The costs for the Board were calculated for each child as being £8 for the passage and £3 10s (£3.50) for an outfit (39). They were sent first to the Emigration Home in Birmingham before embarking on the journey across the Atlantic, and on the 18th June 1885 after a farewell meeting at the Masonic Hall in New Street, Birmingham held by the mayor and attended by several other local dignitaries, 115 children left with John Middlemore for Liverpool. The following day, they set sail aboard the Beaver Line steamer ‘Lake Winnipeg’, arriving in Quebec on the 1st July 1885 before travelling onto the Middlemore Receiving Home at Guthrie House in London, Ontario. From here, the children were sent out to their new homes. Approximately 5,200 children out of the 100,000 plus who were sent to Canada, emigrated through the Middlemore Home between 1873 and 1932. The idea to give destitute children a new start often fell short in reality with some children treated as little more than slave labour in their new placements.

Walter was first sent to a farmer at Chatsworth, Ontario, about 100km north-west of Toronto. ![]() Still only aged about 12, Walter was described in a rather conflicting follow-up report as ‘honest, untruthful, stubborn and sulky, and a great source of trouble’ but added ‘showing signs of slight improvement’.

Still only aged about 12, Walter was described in a rather conflicting follow-up report as ‘honest, untruthful, stubborn and sulky, and a great source of trouble’ but added ‘showing signs of slight improvement’.

Around 1887, Walter, aged about 14, moved to Ekfrid township, an expanse of flat farmland in  Middlesex County, Ontario, close to Lake Erie and about 100km east of Detroit, into the guardianship of Scottish farmer Allan McLean. This would prove to be where Walter would settle, raise a family and remain for the rest of his life.

Middlesex County, Ontario, close to Lake Erie and about 100km east of Detroit, into the guardianship of Scottish farmer Allan McLean. This would prove to be where Walter would settle, raise a family and remain for the rest of his life.

On 6th April 1891, the day after England’s Census showed his half-sister Mary Ann in Dorset Street, the Census for Canada noted that Walter, 17, was still living at Ekfrid as a ‘servant’ for 42-year-old Allan McLean and his wife Margaret, 41. There is no record of Allan and Margaret having any children, so perhaps the arrival of Walter had been their chance to have a ‘family’.

On the 30th March 1897, 23-year-old Walter Shiers married Elizabeth Ann Atkinson, also 23, the daughter of Francis and Grace Atkinson from Ontario. Walter and Elizabeth’s first child Allan Gladstone was born on the 21st June 1898, clearly being named after Walter’s ‘stepfather’. A daughter Ellen A, later known as Nellie, followed on 23rd July 1900. The 1901 Census showed the six of them living and working together on Allan McLean’s farm in Ekfrid.

Walter and Elizabeth’s second son Walter Edwin was born on the 31st January 1903, with another daughter Maggie Grace in 1905, no doubt named after Walter’s ‘stepmother’.

Sadly, both of their sons appeared to suffer from some form of genetic condition. Allan died on the 23rd March 1909 age just 10 years from muscular atrophy of seven years duration and bronchitis of one week. Their younger son Walter died on the 19th March 1920 age 17 from progressive muscular paralysis. The boy’s mother Elizabeth had also died young, passing away age 40 on the 16th July 1913 at the Victoria Hospital, London, Ontario from asthenia of twelve months duration.

Despite these terrible losses, the 1921 Census showed the two families still together on Allan McLean’s Ekfrid farm. Allan and wife Margaret were age 72, with Walter, 46, still employed by Allan. Walter’s daughters, Nellie, 20, and Margaret, 16, made up the household.

About 50 years since Walter had moved in as a young lad with the McLeans, Margaret died age  87 on the 8th October 1936. Walter himself passed away nine months later on the 30th June 1937 age 63 from a coronary thrombosis and arterial sclerosis. Allan died later that year on the 24th December age 88. All three were interred in Longwoods Cemetery, Melbourne, Middlesex – Margaret and Allan in one grave and Walter, buried on the 2nd July 1937, in the same grave as his wife and sons.

87 on the 8th October 1936. Walter himself passed away nine months later on the 30th June 1937 age 63 from a coronary thrombosis and arterial sclerosis. Allan died later that year on the 24th December age 88. All three were interred in Longwoods Cemetery, Melbourne, Middlesex – Margaret and Allan in one grave and Walter, buried on the 2nd July 1937, in the same grave as his wife and sons.

Walter had lost both his parents before his sixth birthday, but his second ‘family’ lasted half a century and enabled him to make something of his life, showing that for him at least, the British Home Children scheme had been a success. As for his half-sister Mary Ann, we may never know if she was ever able to escape the darkness that enveloped her life.

February 2023

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk / Ancestry.com / Fold3.com

CanadianBritishHomeChildren.weebly.com

Centrepoint.org.uk

FindAGrave.com

FindMyPast.co.uk / BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk

General Register Office GRO.gov.uk

Google.co.uk/books

Library and Archives Canada Bac-lac-gc.ca

Legislation.co.uk

Leicestershire and Rutland Record Office

London School of Economics Booth.lse.ac.uk

The Charlotteville Trust Guildford (booklets on the Workhouse) Charlotteville.co.uk

TheGenealogist.co.uk

Wikipedia.org

Workhouses.co.uk

For a full list of references click here