eliza mayers

Subject : Eliza MAYERS née Goddard, aka Eliza Baynes (b 1813 – d 1883)

Researcher : Diann Arnfield

Compton girl lives under stigma of Uncle’s hanging; later marital strife leaves her stranded

Eliza Goddard grew up in Compton with her family living under the stigma of her uncle having been hanged for murder. She married tailor George Mayers, settling with him and their family in central London, but by the time her husband died after more than 20 years of marriage, Eliza had already moved out to live nearby with another married man. This did not last as he disappeared, Eliza being left alone in a London workhouse before being transferred to the Guildford Union Workhouse.

Eliza was born around 1813 in Compton, Surrey, and baptised at the village’s St Nicholas Church on 13th June 1813 1. She was the third of four known children for labourer James Goddard and Elizabeth née Cooper 2, 3, 4, 5.

Eliza was born around 1813 in Compton, Surrey, and baptised at the village’s St Nicholas Church on 13th June 1813 1. She was the third of four known children for labourer James Goddard and Elizabeth née Cooper 2, 3, 4, 5.

Eliza’s uncle sentenced to death

The family were living under a dark cloud in their small village, following the hanging of Eliza’s maternal uncle James Cooper four years earlier for the murder of his landlord 6, 7, 8.

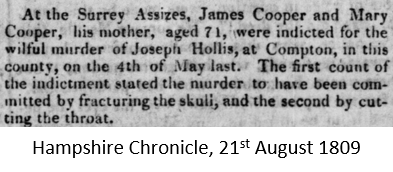

In August 1809, the Surrey Assizes in Croydon heard that on 4th May 1809, 69-year-old Joseph Hollis, owner of a Compton cottage divided into two where he lived in one half, and James Cooper and his mother Mary (Eliza’s grandmother) lived in the other, had been brutally beaten to death with a poker, his throat had been cut with a knife ‘as to nearly sever the head from the body’, leaving his body ‘shockingly mangled’.

In August 1809, the Surrey Assizes in Croydon heard that on 4th May 1809, 69-year-old Joseph Hollis, owner of a Compton cottage divided into two where he lived in one half, and James Cooper and his mother Mary (Eliza’s grandmother) lived in the other, had been brutally beaten to death with a poker, his throat had been cut with a knife ‘as to nearly sever the head from the body’, leaving his body ‘shockingly mangled’.

It was revealed at the trial that two weeks earlier, in a heated argument, that James Cooper had argued with Joseph Hollis for not paying his rent. Joseph Hollis owned several properties in Compton and was not particularly popular as he used to flaunt his money. When he increased the rent and threatened eviction of his tenants James and Mary Cooper, James plotted his demise. James told his mother that he wanted to get ‘upsides’ (even) with Joseph and would do the same to her if she told anyone of his intention. Mary’s alleged response was: ‘It is no great matter, for nobody likes the old fellow’.

Witnesses at the trial stated that the poker and knife used in the fatal attack were owned by James. Bloodstained clothing of his had also been found in his part of the cottage, so the jury found James guilty, and he was given the death sentence. His mother Mary was found not guilty as she had played no part in the murder.

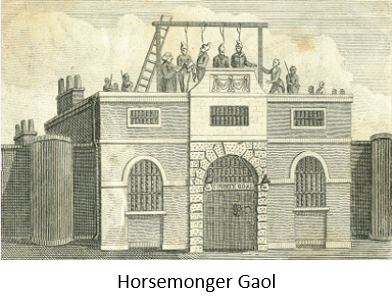

James was taken to Surrey’s County Horsemonger Lane Gaol in Southwark, where he was publicly hanged on 16th August 1809 9. This took place on the Gaol’s gatehouse roof in the hope it would act as a deterrent and would have been watched by a large number of spectators. The execution of a husband and wife there in 1849 attracted a crowd of 40,000 people, including author Charles Dickens, who was appalled by the spectacle.

James was taken to Surrey’s County Horsemonger Lane Gaol in Southwark, where he was publicly hanged on 16th August 1809 9. This took place on the Gaol’s gatehouse roof in the hope it would act as a deterrent and would have been watched by a large number of spectators. The execution of a husband and wife there in 1849 attracted a crowd of 40,000 people, including author Charles Dickens, who was appalled by the spectacle.

Whether anyone from Compton made the 35-mile (56km) journey to Southwark to witness the gruesome event is not known but is easy to imagine the stigma that Eliza and her family are likely to have endured in such a small community.

Marriage and a move to central London

Eliza was still a child when her mother Elizabeth died in September 1820 aged just 46, leaving her labourer father James with 7-year-old Eliza and her siblings George (12) and John (5) 10. Their eldest sister Amelia had married the previous year but remained in Compton with her husband so she may have helped look after the children so their father could earn a wage 11, 12.

Around the age of 18, Eliza married George Mayers, a tailor from Godalming, some ten years older than her, in August 1831 at St John the Evangelist Church, Stoke next Guildford 13, 14.

They settled in Godalming where three children were born, Elizabeth in 1832, George in 1834 and Eliza in 1836/7, all baptised at the St Peter and St Paul Church 15. Elizabeth passed away in June 1833 age 8 months 16.

By 1841, the family had moved to Great Windmill Street, Westminster, London 17. Like today, this was the heart of the capital, but life proved to be tough for them. In 1843, Eliza gave birth to twins, Edwin on 8th April and Emma the following day. Emma died less than four months later from ‘exhaustion from diseased digestive organs’ with Edwin succumbing to ‘cholera’ in August 18, 19, 20. A further son, Thomas, was born in 1846, but he died at home in February 1848 from smallpox 21, 22. The death certificate noted Thomas had not been vaccinated – smallpox vaccination for children was not made compulsory until 5 years later 23.

By 1841, the family had moved to Great Windmill Street, Westminster, London 17. Like today, this was the heart of the capital, but life proved to be tough for them. In 1843, Eliza gave birth to twins, Edwin on 8th April and Emma the following day. Emma died less than four months later from ‘exhaustion from diseased digestive organs’ with Edwin succumbing to ‘cholera’ in August 18, 19, 20. A further son, Thomas, was born in 1846, but he died at home in February 1848 from smallpox 21, 22. The death certificate noted Thomas had not been vaccinated – smallpox vaccination for children was not made compulsory until 5 years later 23.

Soon after this, the family moved around the corner to Rupert Street. The 1851 Census showed there were 23 people living at number 15 including 37-year-old Eliza, George, 47, and their two children 24. 16-year-old George was an apprentice engraver while Eliza, 14, was a dressmaker’s apprentice. George senior’s occupation was described as a ‘tailor journeyman’, meaning that he was employed on a day-by-day basis, the term derived from journée, the French word for day 25.

Eliza swaps husbands

Just two years later, Eliza was widowed when George died in March 1853 from bronchitis and phthisis (tuberculosis), aged 49, at his 15 Rupert Street home 26. However, the informant on the death certificate was not Eliza Mayers, but ‘Suzana Mayers’ who had been present at the death.

The 1861 Census gives some clue as to what may have been going on. It recorded Eliza as ‘wife’ of William Baynes, a printer reader, living in King Street, Westminster, just a short walk from 15 Rupert Street 27. Ten years earlier, that Census had shown William Baynes and his wife Susannah had also been living at 15 Rupert Street, so had Eliza gone off with William Baynes leaving Susannah (Suzana) Baynes with Eliza’s husband George 28?

No marriage record has been traced for Eliza Mayers and William Baynes, or for George Mayers and Susannah Baynes.

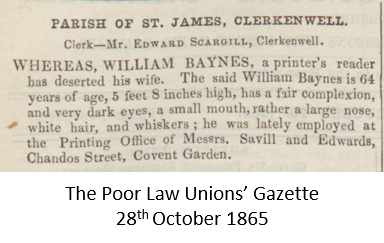

Susannah, although not traced on the 1861 Census, remained in London after George’s death. She passed away in Clerkenwell Workhouse in November 1866. She would have entered that Workhouse at least over a year previously, as the Poor Law Unions’ Gazette had been publishing a request for information on the whereabouts of her missing husband William Baynes who had ‘deserted his wife’ since Autumn 1865 29, 30. This request was regularly repeated in the Poor Law Unions’ Gazette until early 1869, over two years after Susannah’s death, and was an attempt by Clerkenwell to recoup costs 31. It is not known if Clerkenwell Union received notice that William had died by 1869, or if they just stopped chasing him. No death record has been found for him.

Susannah, although not traced on the 1861 Census, remained in London after George’s death. She passed away in Clerkenwell Workhouse in November 1866. She would have entered that Workhouse at least over a year previously, as the Poor Law Unions’ Gazette had been publishing a request for information on the whereabouts of her missing husband William Baynes who had ‘deserted his wife’ since Autumn 1865 29, 30. This request was regularly repeated in the Poor Law Unions’ Gazette until early 1869, over two years after Susannah’s death, and was an attempt by Clerkenwell to recoup costs 31. It is not known if Clerkenwell Union received notice that William had died by 1869, or if they just stopped chasing him. No death record has been found for him.

There are also no records available to indicate whether Eliza had continued to live with William Baynes after 1861, or if he deserted her as well. In 1869 she was in the Broad Street Workhouse, Holborn for at least 2 stays 32, 33. The 1871 census listed Eliza, still using the surname ‘Baynes’ there as a 57-year-old widow born in Compton, profession ‘needlework’, and there was a further entry for her in October 1872 34, 35.

Removed back to Guildford

Eliza may have been simply struggling to survive, or perhaps more likely she had been admitted to the Workhouse Infirmary from time to time for treatment, or a combination of both. In May 1873 she was once more admitted to the Broad Street Workhouse 36. This time, in August 1873 Broad Street Workhouse arranged for Eliza to be removed to Guildford 37. Having been born in Compton, and married to a Godalming-born man, by law the responsibility and cost for Eliza’s care lay with the Guildford Union, and as an elderly lady in her 60s probably requiring long term care Broad Street would have been keen to have her off their books.

Eliza remained in the Guildford Union Workhouse for the rest of her life. Although she was transferred under the surname ‘Baynes’, the 1881 Census recorded her there as Eliza ‘Mayers’, 69, a widowed domestic servant 38. She passed away in the Workhouse on 12th April 1883 from ‘asthma and dilated heart’, aged 72 and was buried at Godalming’s Nightingale Cemetery five days later 39, 40.

November 2022, updated September 2025

Edited by Mike Brock

We’d love to hear from you if you are a relative of this family.

Please contact us by email: spikelives@charlotteville.co.uk

Sources and References

Original Surrey parish records and newspapers are available at the Surrey History Centre, Woking. Ancestry.co.uk and British Newspaper Archive/FindMyPast.co.uk were used for digitised records online. A complete list of references may be found here Eliza Mayers References

Spike Lives is a Heritage project that chronicles the lives of inmates, staff and the Board of Guardians of the Guildford Union Workhouse at the time of the 1881 Census. The Spike Heritage Museum in Guildford offers guided tours which present a unique opportunity to discover what life was like in the Casual/Vagrant ward of a Workhouse. More information can be found here

Spike Lives is a Heritage project that chronicles the lives of inmates, staff and the Board of Guardians of the Guildford Union Workhouse at the time of the 1881 Census. The Spike Heritage Museum in Guildford offers guided tours which present a unique opportunity to discover what life was like in the Casual/Vagrant ward of a Workhouse. More information can be found here