Stephen Barry

Subject Name: Stephen Barry (aka John Barry, Stephen Barrett) (b 1799 – d 1886)

Researcher: Heather Turner

Stephen Barry came from Mallow, Cork, Ireland and was probably born in 1799 to Philip Barry and Mary (Margaret) Ronayne of Rathcormack, near Mallow. His baptism is likely to have taken place on 6 December in the same year at Saints Peter and Paul, Catholic church, Cork city, Ireland. The church was built in 1786 and at that time was known as Carey’s Lane Chapel and was the parish Church for the entire centre of Cork City. The current Church of Saints Peter and Paul is now located just off St Patrick’s Street in the centre of Cork City and is regarded as one of the finest examples of 19th century neo-Gothic architecture in Ireland.

Although it’s not clear when Stephen came to England, on the 1841 Census, Stephen is in Liverpool with his wife and five children and is working as a labourer. Many Irishmen at that time, came over to mainland Britain looking for labouring work on the construction projects of roads, railways, and canals and were commonly known as navvies (navigators). Stephen would have found it quite difficult to stay employed though as at that time, there was a lot of prejudice towards Irish people and Liverpool was known as the ‘capital of violence’. Living conditions in Liverpool were very poor even as recently as the 1960s and stories of abject poverty and domestic abuse are common. In the 1970s and 80s vans still drove to Short Street in Liverpool containing about 100 navvies who were looking for work. Employers would be looking for men that fitted the build for a ‘banjo’ which is slang for a shovel.

As Stephen got older, he would have found it more and more difficult to find work as the employers chose younger and fitter men. Stephen and his family are likely to have suffered great hardship and given Stephen’s age and physical condition, he would have found it hard to get legitimate work. This could be why Stephen turned to a life of crime, being convicted and imprisoned four times between 1857 and 1871. The latter sentence being imprisonment for 10 years.

Although the full details of the crimes committed in 1857 and 1858 cannot be found, he was convicted in February 1857 using the alias of John Barry and received nine months imprisonment. A year later, again using an alias, but this time Stephen Barrett, he received a prison sentence of four years for his crime. Stephen would have used aliases to avoid the police catching up with him and probably spent his life ‘looking over his shoulder’.

On 8th April 1862, John Barry alias Stephen Barry, age 63, once again found himself in front of a judge at the Middlesex Sessions. He was accused of ‘Unlawfully Uttering Counterfeit Coin well knowing the same to be counterfeit’ to which he pleaded guilty to. Uttering is the crime of knowingly tendering or showing a forged instrument or counterfeit coin to another with intent to defraud. He was sentenced to six years penal servitude to be served in Millbank Prison but on the 2nd January 1863, for reasons unknown, he was removed to Portsmouth Prison.

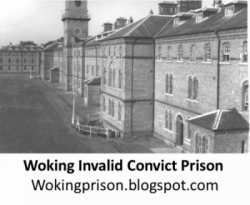

Stephen clearly didn’t learn any lessons from his time in prison as on 9th January 1871 at the age of 74 he was at the Old Bailey having been accused again of Uttering Base Coin. On this occasion, he tried to pay for a quartern of rum in the Devonshire Arms in Kensington with a ‘bad coin’. During the trial he claimed that he did not know the coin was ‘bad’ but given his known previous conviction in 1862 for the same crime, he was sentenced to 10 years ‘penal servitude’ plus 7 years police supervision and sent to Newgate Prison.  The following month, he was transferred to Millbank Prison and later that year, on 20th October he was moved to Woking Invalid Prison where he completed his sentence. This prison was specifically built for invalid and infirm convicts and was opened in 1860. During his time there, records describe Stephen as being ‘rather delicate’ and his conduct as ‘very good’.

The following month, he was transferred to Millbank Prison and later that year, on 20th October he was moved to Woking Invalid Prison where he completed his sentence. This prison was specifically built for invalid and infirm convicts and was opened in 1860. During his time there, records describe Stephen as being ‘rather delicate’ and his conduct as ‘very good’.

Stephen was finally released from prison on 8th January 1881. On his discharge, the records show that he was born in Cork in the late 1790s and his trade was a labourer. Although there is no photo of Stephen, the records help to paint an image of him, stating he was 5’ 4’’ tall and of slender build. He had an oval face with a fair complexion, grey hair and light blue eyes. His right little finger was broken, he had an injured ankle, was blind in his left eye and all his toes were deformed. Clearly, he was a man that was in fairly poor condition and it’s not clear how he sustained some of these injuries. Although it is not known who his wife was, or when she died, he was described as being a widower and by order of the Home Office, via a letter from the governor of Woking invalid Prison at Knaphill, he was to be sent to the Guildford Union Workhouse as his place of settlement could not be ascertained.

The decision to relocate him to the Guildford Workhouse caused some consternation between the Guildford Board of Guardians as they felt that they should not automatically be liable to take in every convict from Woking Invalid Prison whose settlement place could not be identified. Consequently, the Chairman of the Board of Guardians instructed the Master of the Workhouse, to whom the letter was sent, to write to the Governor of the Prison and say that he could not take in Stephen Barry without an order from the Relieving Officer. The Relieving Officer subsequently went to the prison and found that the man was 81 years of age, an invalid and almost bedridden. The Board of Guardians understood that given the helpless condition of the convict it would make it impossible to adopt any other decision but to take him in. For Stephen, this decision was probably a blessing as if they had refused to take him in, he could have found himself homeless and who knows what could have happened to him.

Nevertheless, the Chairman of the Board of Guardians, who was described as ‘energetic’, decided to personally interview the Home Office authorities. This resulted in them agreeing that in the future, whenever practicable, these invalid convicts should be discharged to the jurisdiction within which their offence was committed. In addition, the parishes’ authorities, who were required to receive them, would have a full explanation of the circumstances of the case and the reasons for sending the convict to their care.

Despite his tough life, Stephen lived to a great age dying in the Guildford Workhouse on the 21st July 1886 at the age of 87. His death certificate states that he died of “decay of age” which in modern terms, essentially means old age. Sadly, his burial site is currently unknown.

December 2019

Sources : A History of Woking by Alan Crosby

Ancestry.co.uk

British Newspaper Archive

General Register Office

Old Bailey Online

Saint Peter and Saint Paul’s Catholic Church, Cork

Surrey History Centre

The Genealogist

Full references available here