SIDNEY ATTFIELD

Subject Name: Sidney Attfield (b 1840 – d?)

Subject Name: Sidney Attfield (b 1840 – d?)

Researcher: Diann Arnfield

Sidney Attfield’s lonely life, despite being one of 13 children, saw him in prison and the workhouse, and after a spell in India with the British Army, he returned with poor health to face more hardship before disappearing from records.

Sidney was born in Albury, Surrey on 3rd May 1840, the ninth child of John and his second wife Ann Attfield, nee Holland. He was baptised at the village’s St Peter and St Paul Church on 14th June 1840.

Life was undoubtedly harsh for the family. Three years before Sidney’s birth, his father had applied to the Poor Law Commissioners at Somerset House, London, requesting that the Guildford Union Workhouse take in his two eldest sons who were very ”weakily”.

However, the 1841 Census showed that all nine children, from one-year-old Sidney to the oldest, Henry, 14, were living under one roof in Albury with their parents John, a 50-year-old agricultural labourer, and Ann, 35.

The family didn’t stop growing as four more children were born – John in 1842, David in 1843, Clara in 1846 who sadly only lived for three weeks, and James, the 13th child, in 1847. Both David and James were dwarfs.

Tragedy was soon to turn the family’s lives upside down, as Sidney’s mother Ann contracted phthisis (tuberculosis), passing away in Albury on 9th November 1848 age 46. This left her husband John in an almost impossible situation, having six children age ten or less, including eight-year-old Sidney, to care for, while still trying to earn a wage.

Despite this, the 1851 Census showed that John, 63, was still head of the family home in Albury with eight of his children aged from 24 down to three. He was receiving parish relief while still working as an agricultural labourer. Sidney, though, was one of two of the younger children not living there. The nine-year-old (actually almost 11), along with his 13-year-old sister Sophia, were paupers residing in the Guildford Union Workhouse. Why only Sidney and Sophia were separate from their family is not known.

Following the traumas of his mother’s death and being sent to the Workhouse, it is maybe not surprising that Sidney was soon in trouble with the authorities. On 8th September 1856, 16-year-old Sidney broke into a house in Smithwood Common, Cranleigh and stole two loaves of bread, a pound of sugar, a saucepan and a gold ring. He was arrested two days later on Albury Heath by PC Bridger, who told the County Bench sessions in Guildford on 20th September that Sidney had taken him to where the saucepan had been left in the warren (woodland). Sidney admitted to boiling up the sugar with some blackberries in the saucepan which he then ate with the bread, saying that he had committed the theft “from hunger”. He then told the policeman of other houses he had broken into. Sidney pleaded guilty, going on to say that he had been in the Guildford Union once (as noted in the 1851 Census) but had run away. He said that his father lived in nearby Farley Heath with a woman keeping the house as Sidney’s mother had died. Sidney went on to say that his father had turned him out of the house as he “had to work”.

All this seems to indicate that Sidney did not have a home to go to. The chairman of the Bench remarked to Sidney that his father “was more culpable than himself”. Despite this, he ruled that Sidney would receive a two-month prison sentence “to prevent him stealing for the future”.

Unfortunately, this did not have the desired effect. The West Surrey Times of 10th October 1857, reported that Sidney, “well known by his frequent appearance at this court”, was charged with absconding from the Workhouse on 25th June, taking with him workhouse clothing. Sidney had been there since his release from Wandsworth prison the previous year. He was said to have been “guilty of improper conduct” at the Workhouse, for which the schoolmaster had threatened punishment, leading to him absconding. Sidney was only just out of gaol after stealing a pair of shoes, so the Chairman of the Bench decided to sentence him to 48 hours in solitary confinement in the Workhouse on bread and water.

This relative leniency didn’t pay off, as on 14th February 1858, “a young incorrigible” Sidney fled the Guildford Workhouse “for not the first, second or third time” only to be caught and given a one-month prison sentence.

Soon after his release, Sidney was in trouble yet again after two housebreaking robberies on 1st May and 21st June 1858, only this time the outcome was far more serious. The 18-year-old was brought before the Guildford Summer Assizes where he was charged with “Feloniously and burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling house of Sarah Kaile, at Albury, and stealing therein one tin canister, and one coat, her property.” Sidney pleaded guilty to the charge and was sentenced to 18 months hard labour in Wandsworth Prison. At that time, he gave his occupation as a shoemaker, although there is little evidence to support this.

Sidney would have been released from Wandsworth in early 1860. In October that year, his life took another turn when, age 20, he signed up in Guildford for the British Army’s 1st Battalion of the 15th Foot Regiment, which at the time was based at the Curragh, Ireland. This would guarantee him food and a bed, and may have been his incentive to enlist.

Sidney spent over a year with the Regiment in Ireland, including a week in gaol in June 1861 for an unspecified offence. He was transferred in April 1862 to the 2nd Battalion of the 15th Foot Regiment in Malta (20), before his final move in 1863 to the 103rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Bombay Fusiliers) in India, based in the north-west of the country, in Bombay, Neemuch and Morar. This was a difficult time in the country, coming less than five years since the Indian Rebellion against British rule had ended.

Sidney was in India for two and a half years, before returning to the Regiment’s English base at Shorncliffe Army Camp in Kent. His health was giving cause for concern, and on 1st April 1867, he was “found medically unfit for further service”. The Inspecting Medical Officer attributed Sidney’s ill-health to “epilepsia” but added that “we have no proof of his actually having fits”. A maybe more telling paragraph came at the end of the report which said that Sidney had a “constitutional tendency called into action by an excessive use of tobacco” and “has been under the influence of intoxicating liquors”.

Sidney stepped back into civilian life after more than six years in the Army and with a meagre pension of 7d (about 3p) per day (24). His Army record said that his “conduct has been good, and he is in possession of one good conduct badge” but would this continue?

It would seem not, as on the 18th June 1867, Sidney stole – and then returned – two shillings (10p). In a somewhat bizarre incident, Sidney had visited Ann Sutlieff in Bell Field, Stoke and she invited him to stay for dinner. She then left her house to meet two of her four children, leaving Sidney in care of the other two. When she returned, Sidney was leaving through the garden gate, saying he was going “to meet the postman”. On going inside the house, Ann discovered that a two-shilling piece that had been hidden under an egg-cup had been taken, so she ran after Sidney and asked him to return the coin, which he did. Despite this, Ann reported the incident, resulting in Sidney being sentenced to serve three more months in gaol.

On leaving the Army, Sidney had noted his intention to live in Guildford High Street, which he may well have done, but the Guildford Union Poor Law Record also showed that he was in the Union Workhouse for a total of 17 days in the half-year ending 29th September 1867 with three more days there in the next six-month period up to 25th March 1868.

Sidney’s name appears in the admission register for the Camden/St Pancras Workhouse on 29th January 1868, and a week later he was re-admitted as ”ill”. His reasons for travelling to London are not known, but he was discharged from that Workhouse over six months later on 27th August 1868, being referred to the Medical Officer for a report.

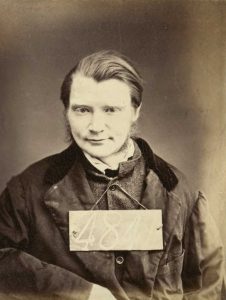

No records have been found of Sidney for the following five years including the 1871 Census, until he was committed at Guildford on 1st March 1873 for stealing seven onions – a small theft that saw him sentenced to three months imprisonment. His record, including a striking photograph of him wearing his prison number 4841 (above), was entered into the Metropolitan Police Habitual Criminals Register (29). That noted that Sidney had “no home” and that his intended place of residence after his scheduled release on 31st May 1873 was the Guildford Union. He was admitted to the Holborn Workhouse on 13th April 1874 on doctor’s advice, leaving on his own request on 20th July 1874.

It looks like Sidney was now well and truly a vagrant, homeless since leaving the army, with health issues, wandering between Guildford and London.

The 1881 Census saw Sidney back at the Guildford Union, listed as an unmarried 38-year-old ”vagrant”. His trade was given as a baker, although there are no other records to verify this line of work. The Workhouse had strict rules for vagrants. They were permitted to stay for one night only, and then do a morning’s work to pay for their keep before being moved on. They were checked on entry for alcohol and other banned substances and had to take a bath and have their clothes disinfected. They were then given a meal and a bed for the night, in narrow, individual cells, which they were locked in until the following morning. The work involved picking oakum, chopping wood or breaking rocks for roadmaking. Inmates were expected to push the broken rocks through the grille of their cell, to ensure the stones were sufficiently small. These grilles can still be seen at the Guildford “Spike” Workhouse Museum.

That 1881 Census, taken on the night of the 3rd April, is the last record found of Sidney’s life – he simply just disappeared. His prospects as he left the Guildford Union the next day would’ve been bleak – he had no home, no immediate family to call on and almost certainly very poor health, despite being only 40. What became of him can only be speculated on, but it is hard to think of a positive outcome for someone whose life had been a constant battle with poverty, the authorities and his own health.

February 2020, updated May 2022

Sources : Ancestry.co.uk

Exploring Surrey’s Past, exploringsurreyspast.org.uk

Findmypast.co.uk / British Newspaper Archives

General Register Office gro.gov.uk

Surrey History Centre, Woking, surreycc.gov.uk/culture-and-leisure/history-centre

The Spike Heritage Centre, guildfordspike.co.uk

Full references available here.