MARTHA CORNISH

Subject Name: Martha Cornish (b1798 – d1882)

Researcher: Christine Clarke

Martha Cornish’s husband fell victim to one of London’s devastating cholera epidemics, as did her step-daughter Sarah’s husband five years later, but a strong bond between Martha and Sarah helped see them through this terrible time.

Martha Perryn was born about 1798, the youngest of six children of John Perryn, a breeches maker, and Mary, née Willies. She was baptised on 16th December 1798 in the 14th Century St Helen’s Chapel in Witton-cum-Twambrooks, now part of Northwich in Cheshire. Little else is known about her early life.

Martha next appears in official records on 5th January 1826 when she married William Cornish, a hatter, in the Collegiate Church of Manchester, which later became Manchester Cathedral. Both signed their name on the certificate.

William was a widower with a daughter, six-year-old Sarah. His first wife, Mary Ann Lewtas, had died on 19th February 1822 of “a decline”, age 24. He had also suffered the loss of his two other children, Richard age 4 in 1821 and Elizabeth, 20 months, in 1822 just seven months after his wife had passed away. All three burials took place at the non-conformist New Jerusalem Temple in Salford, although the children had been baptised into the Church of England.

There are no records to indicate that Martha and William had any children of their own, but it is clear that in later years Martha became very close to her step-daughter Sarah, even being listed as her “mother” on two Census returns.

At some stage, possibly for work reasons, the family relocated to London. The 1841 Census shows Martha, 42, and William, a 40-year-old hatter, living in Duke Street (now known as Duchy Street), Waterloo, London. Their street was mostly inhabited by tradespeople including carpenters, a painter, printer, compositor, bookbinder, furrier, milliner, hat finisher and dyer. William’s age was more likely about 50. The area was historically associated with hat making. The company Christy’s, the largest hat and cap making factory in the world in the 1840s, had a factory in Bermondsey, so perhaps William was working there.

William’s daughter Sarah was close by – she had married stationer Henry Chaplin on 4th May 1840 at St. Olave’s, Southwark. They were living with their first child, ten-week-old Lucy at 16 Webb Street, Southwark.

Unfortunately for the family, although they were living in a fairly comfortable area, their surroundings on the South bank of the Thames were rife with disease, including cholera which had first struck London in 1831. With little understanding of what caused cholera, a second major outbreak hit London, and especially Bermondsey, in 1848/9, taking the life of Martha’s husband William on 16th

September 1849 age 57. His non-conformist burial took place on 17th September at the Southwark Wesleyan Chapel in Bermondsey.

Eight days following William’s death, a graphic account of the terrible conditions in Bermondsey was published by the Morning Chronicle newspaper. Author Henry Mayhew, a noted social researcher, wrote that in just the past three months,  12,800 people had died of cholera. “6,500 have occurred on the southern shores of the Thames; and to this awful number no localities have contributed so largely as Lambeth, Southwark and Bermondsey, each, at the height of the disease, adding its hundred victims a week to the fearful catalogue of mortality. Anyone who had ventured a visit to the last-named of these places in particular, will not wonder at the ravages of the pestilence in this malarious quarter, for it is bounded on the north and east by filth and fever, and on the south and west by want, squalor, rags and pestilence.”

12,800 people had died of cholera. “6,500 have occurred on the southern shores of the Thames; and to this awful number no localities have contributed so largely as Lambeth, Southwark and Bermondsey, each, at the height of the disease, adding its hundred victims a week to the fearful catalogue of mortality. Anyone who had ventured a visit to the last-named of these places in particular, will not wonder at the ravages of the pestilence in this malarious quarter, for it is bounded on the north and east by filth and fever, and on the south and west by want, squalor, rags and pestilence.”

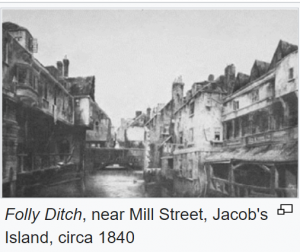

Mayhew’s investigation centred on a notorious area known as Jacob’s Island, just a few hundred  metres from where William had died in Grange Walk, Bermondsey. Charles Dickens used the location of Folly Ditch in Jacob’s Island for the death of the character Bill Sikes in his 1837 novel “Oliver Twist”, describing “dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage: all these ornament the banks of Jacob’s Island”.

metres from where William had died in Grange Walk, Bermondsey. Charles Dickens used the location of Folly Ditch in Jacob’s Island for the death of the character Bill Sikes in his 1837 novel “Oliver Twist”, describing “dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage: all these ornament the banks of Jacob’s Island”.

Although the belief had been that the quality of the air was the cause of cholera, studies by doctor and anaesthetist John Snow in 1849 indicated that contaminated water was the actual cause. It was not until after another epidemic in London five years later, which caused a further loss for Martha, that he was able to begin to find evidence for his theory.

Despite the ravages of cholera, Martha remained in the Bermondsey area after her husband’s death and without an income, she would now have needed to earn money herself. Eighteen months later, the 1851 Census showed 50-year-old Martha employed as a housekeeper for a young couple, Charles T. Braham, a manufacturing chemist, and his wife Emma Mary, at 9 Alfred Street, Bermondsey. Martha’s step-daughter Sarah, age 32, was living a short distance away at 213 Bermondsey Street with husband Henry, a 32-year-old stationer and printer. They had five children aged between ten years and four months. Henry was clearly earning good money as he was employing two live-in domestic servants. He had also inherited £600 following his father Thomas’s death in 1846.

In 1854, the third cholera epidemic hit London with the Bermondsey area once again one of the worst affected. This time, Sarah’s husband Henry, age just 35, was another victim, passing away on 31st August. Sarah was expecting her seventh child – a sixth, Sarah, had been born in 1853.

Henry’s will showed that he owned four properties in Salisbury Lane, Bermondsey and that the money earned from the rent would be used to maintain Sarah and the family. However, Sarah would still have needed to make some savings, so it is likely that the two servants would not have been retained. Martha would undoubtedly have wanted to move in to help Sarah with bringing up the family and this seems to have been the case as Sarah honoured her step-mother by naming her seventh child Martha Jane, born in 1855.

The 1861 Census confirmed that 61-year-old Martha was living with 42-year-old step-daughter Sarah, a “printer’s widow”, and Sarah’s five children at 144 Grange Road, Bermondsey. Martha, no longer employed, was noted as “mother” to Sarah. Three of Sarah’s children were now working – Lucy, 20, was a schoolmistress, Thomas, 16, a leather warehouseman and Henry, 15, a clerk in a leather factory. The other two were William, 13, and six-year-old Martha. Two of Sarah’s children had died – Sarah age 4 in 1857 and Joseph, 7, early the following year. Thomas Chaplin, a 37-year-old stationer and bookseller, cousin of Sarah’s husband Henry, completed the household.

One interesting but tragic sidenote is that schoolmistress Lucy married Frederick Galpin, a Methodist Free Church Missionary, in 1867. They set off for China to carry on Frederick’s work, setting up a Mission in the Ningbo District just south of Shanghai on China’s east coast, but Lucy died there soon afterwards in 1869, age 28.

The 1871 Census showed Martha still living with Sarah, lodging in the household of George H. Golding, a steward’s office clerk, at 27 Alma Road, Bermondsey. Martha, age 71, was again noted as “mother” to Sarah, 52. Also there were Sarah’s 16-year-old daughter Martha Jane, plus two of Sarah’s grandchildren, Lucy Jane Chaplin age 4 and Sarah Louisa Chaplin age three months. They were daughters of Sarah’s son Thomas, whose 26-year-old wife Mary Jane had passed away a few weeks earlier, soon after giving birth to Sarah Louisa. Sadly, Sarah Louisa also died shortly after the 1871 Census.

Martha Jane married William Thomas Raxworthy in Southwark in mid-1875. Their first two children were born in Rotherhithe, Southwark, in 1877 and 1879, and their third in Woking, Guildford, in 1881.  William, a confectioner and stationer, had been declared bankrupt in April 1879, so perhaps this was why they had moved to Woking. The 1881 Census notes the family living in School Board Road, Woking, and that William was now a commercial traveller. We do not know if Martha Jane’s mother Sarah and step-grandmother Martha had lived with the Raxworthys in Rotherhithe, but it seems very likely, as they certainly moved to Woking at the same time. The family had clearly remained close as Martha Jane’s niece, 14-year-old Lucy Jane Chaplin, who ten years earlier had been living with Sarah’s family after her mother had passed away, was with the Raxworthys in 1881.

William, a confectioner and stationer, had been declared bankrupt in April 1879, so perhaps this was why they had moved to Woking. The 1881 Census notes the family living in School Board Road, Woking, and that William was now a commercial traveller. We do not know if Martha Jane’s mother Sarah and step-grandmother Martha had lived with the Raxworthys in Rotherhithe, but it seems very likely, as they certainly moved to Woking at the same time. The family had clearly remained close as Martha Jane’s niece, 14-year-old Lucy Jane Chaplin, who ten years earlier had been living with Sarah’s family after her mother had passed away, was with the Raxworthys in 1881.

Sarah Chaplin, step-daughter of Martha and mother of Martha Jane, had died just before the 1881 Census, age 62, on 14th December 1880, at 3 Weston Villas, Woking. This address appeared later in local newspaper advertisements in January 1882 for “The Shilling House Club” a house purchasing scheme of which MJ Chaplin (Martha Jane’s maiden name) was the secretary.

The 1881 Census, taken less than four months after Sarah’s passing, showed that Martha had become an inmate of the Guildford Union Workhouse. She was described as an 80-year-old widowed domestic servant born in Manchester.

There are no admission and departure records existing for the Guildford Union Workhouse, but it seems likely that Martha had gone into the Workhouse after Sarah’s death, and had remained there for the rest of her life. She passed away there the following year on 14th December 1882, age 82. Her cause of death was noted as paralysis and “sanguineous apoplexy”, a type of stroke. Martha was buried at St John the Baptist Church, Woking on December 18th 1882.

seems likely that Martha had gone into the Workhouse after Sarah’s death, and had remained there for the rest of her life. She passed away there the following year on 14th December 1882, age 82. Her cause of death was noted as paralysis and “sanguineous apoplexy”, a type of stroke. Martha was buried at St John the Baptist Church, Woking on December 18th 1882.

April 2021, updated September 2022

Christine Clarke, Mike Brock

Sources : Ancestry.co.uk

Be Global Fashion Network magazine bgfashion.net

Bermondsey Street Back Stories Bermondseystreet.london

Christys-hats.com

Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland DMBI.online

FindMyPast.co.uk / British Newspaper Archives

HSomerville.com

Pasttenseblog.wordpress.com

Science Museum Sciencemuseum.org.uk

Surrey History Centre, Woking surreycc.gov.uk

The London Gazette Official Public Record thegazette.co.uk

Wikipedia.org

For a full list of references click here